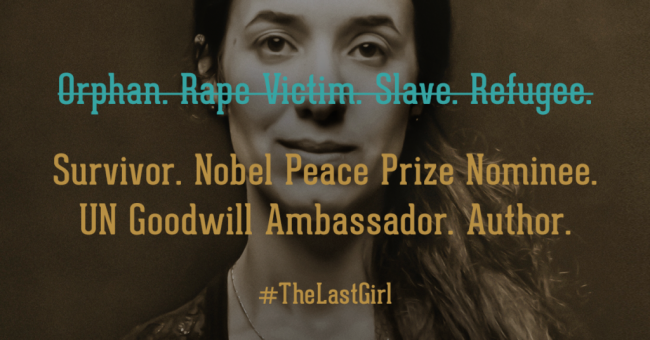

Book: The Last Girl; Author: Nadia Murad; Publisher: Vergo Press/Hachette India; Pages: 306

She suffered at the hands of the Islamic State, was held captive as a sex slave, but went on to become a human rights campaigner and was awarded the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize jointly with Congolese gynaecologist Denis Mukwege. In her memoir, “The Last Girl”, Nadia Murad recalls the dreadful sequence of events that led to her captivity and reflects on the life she has been leading thereafter.

It is a painful story, of a life shattered all of a sudden, that left Murad with little hope of freedom. But it inspired her to visualise a change in the world — with the powerful weapon of her own story as the instrument of change.

In August 2014, Islamic State militants laid siege on Murad’s village, Kocho, in Iraq. The militants showed no mercy and first executed almost all the men and older women, which included Murad’s mother and six brothers. All of them were buried in mass graves as younger women like Murad, who were spared, looked on hopelessly.

The younger women were then kidnapped by the IS militants and were sold as sex slaves, where they were held captive, tortured and raped by several militants. She was barely 21 years old, but the militants knew no mercy.

“The slave market opened at night. We could hear the commotion downstairs where militants were registering and organising, and when the first man entered the room, all the girls started screaming. It was like the scene of an explosion. We moaned as though wounded, doubling over and vomiting on the floor, but none of it stopped the militants,” she recalls in the memoir, first published in the United Kingdom by Virgo Press, and now here by Hachette India.

She adds that the militants paced around the room, staring at them, while they screamed and begged.

“They gravitated toward the most beautiful girls first, asking, ‘How old are you?’ and examining their hair and mouths. ‘They are virgins, right?’ they asked a guard, who nodded and said, ‘Of course!’ like a shopkeeper taking pride in his product. Now the militants touched us anywhere they wanted, running their hands over our breasts and our legs, as if we were animals,” Murad recounts.

After she was sold to a jihadist in Mosul, an opportunity to escape arrived when she found the front door unlocked. Murad escaped to Kurdistan, posing as the wife of a Sunni man, Nasser, who literally risked his life and everything he had to take her to safety.

But the relief did not last long as Murad and Nasser were detained by Kurdish officials and forced to testify about their escape.

“I was quickly learning that my story, which I still thought of as a personal tragedy, could be someone else’s political tool,” she notes.

In early 2015, Murad went as a refugee to Germany and later that year she began to campaign to raise awareness of human trafficking. She was invited to Switzerland to speak at a UN forum on minority issues.

“It was the first time I would tell my story in front of a large audience. I wanted to talk about everything — the children who died of dehydration fleeing ISIS, the families still stranded on the mountain, the thousands of women and children who remained in captivity, and what my brothers saw at the site of the massacre.

“I was only one of hundreds of thousands of Yazidi victims. My community was scattered, living as refugees inside and outside of Iraq, and Kocho was still occupied by ISIS. There was so much the world needed to hear about what was happening to Yazidis,” she writes.

In the memoir, Murad maintains that her story, “told honestly and matter-of-factly”, is the best weapon she has against terrorism. She emphasises that she plans on using it until the terrorists are put on trial, and reminds those in power that there is still so much that needs to be done. She urges the world leaders, particularly Muslim religious leaders, to stand up and protect the oppressed.

Murad says in the book that she wishes to look into the eyes of the men who raped her and see them brought to justice. And she is vocal about her sufferings as well as what she wants the authorities to do because she, as the title of her memoir says, wants to be “The Last Girl” with a story like hers.