By Vishnu Makhijani

Understanding true forgiveness is a personal process that takes place within the heart, a process that takes time to assimilate.

“Numb with shock and disbelief”, the words that floated through the thoughts of Kia Scherr, whose husband and 13-year-old daughter were victims of the 26/11 Mumbai terror attack, as she watched the carnage unfold on her TV screen in Florida, were “Forgive them; they know not what they do” – though it took many years to truly experience “that forgiveness is the light that gets in through the cracks, seeping in through the pieces of my shattered heart”.

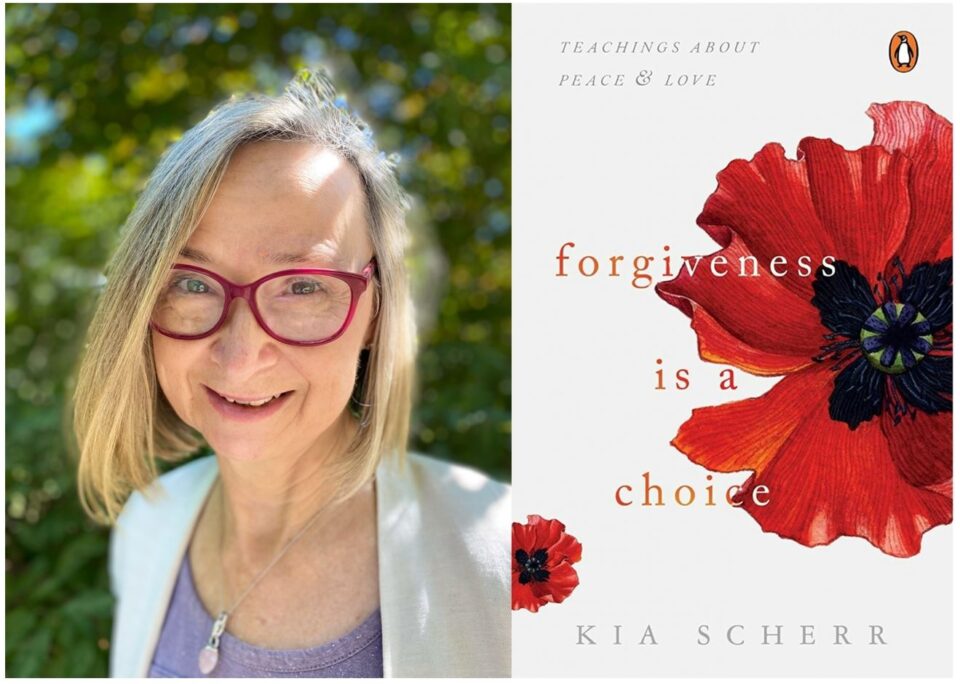

Forgiveness “does not mean pardon, nor does it mean condoning a despicable action, or not holding a person accountable for cold-blooded murder…you are not forgiving a hateful act, you are forgiving that person for forgetting their own goodness and for being incapable of loving”, Scherr writes in “Forgiveness Is a Choice – Teachings About Peace and Love” (Penguin).

In 2009, she founded the One Life Alliance in 2009 in memory of her husband Alan and daughter Naomi and spent over a thousand days in Mumbai over a six year period, propagating its message of compassion, forgiveness and respect for life among communities, schools, businesses – and an enthusiastic police force.

“Forgiveness is a personal choice to accept what cannot be changed, however hurtful. Forgiveness has nothing to do with the terrorist (in this case Ajmal Kasab, the lone survivor of the Mumbai attack whose visuals Scherr saw on TV). I have no personal relationship with that terrorist, other than we are both human beings. Do I want to hold on to anger, resentment, feelings of revenge and retaliation,” the author asks.

“Forgiveness allows me to keep my heart open so that I can continue to love the life I’m now living. This is how I choose to honour the memory of Alan and Naomi. I have chosen to create a living memorial that brings the possibility of peace, compassion and love to this world. This is what gives me purpose and allows me to keep living, to keep loving, and to open myself to a greater vision for humanity that could create an environment for positive change,” Scherr writes.

This would mean a society where life is valued above all else, she adds.

“This would mean a major transformation of priorities for most of the world. This is another kind of ‘climate change’. We could create a climate of mutual love and respect, which forms the foundation of another way to evaluate our conflicts and resolve our differences. It would mean collaborating in new ways and communicating truthfully with an intention to work things out with integrity” Scherr writes.

Admitting that this “sounds utopian” she firmly believes that “we can move in this direction to honour the sacredness of life we share, to live it, breathe it and celebrate it”.

“We can each be more loving in a thousand different ways. If I can be more loving by forgiving the terrorist who killed mu husband and my daughter. I can start living again. Now I can renew my life, a life that does not include Alan and Naomi. But it does include the love for them that will never die. Why else are we here if not to love? Without love, what’s the point? When Alan and Naomi were killed, love remained. When my mother died of lung cancer, love remained. A part of me died with each of their deaths, but love remained. Love is the core ingredient of this human life. Love is our greatest natural resource. There is no end to love unless we close the door to our hearts,” Scherr firmly maintains.

To this extent, the book outlines 30 practices that the author used to renew her life “after a major loss that turned everything upside down”.

“Forgiveness was the key that kept my heart open to love, but we don’t begin with forgiveness. We want to lead up to forgiveness after we have reached some understanding and acceptance of what has happened. The ultimate outcome is increasing your experience of love, so it’s worth taking this step day by day,” Scherr writes, adding that to gain the full benefit of these simple practices, it is best to focus on one practice at a time, day by day or even longer even though the book can be read at one stretch.

She terms this “30-day peace pledge book” a “tool to remind ourselves to honour the dignity of life in each and every moment. Not only is it helpful for one to read it individually, it is helpful to take the pledge with others in our lives and with our communities. When we start with this pledge, we begin to transform how we see ourselves and others. Used in classrooms, it can be an effective various curricula and disciplines to reduce and eliminate bullying, build student self-esteem and develop their focus in their work and at home”.

In all this, it would seem an irony that Alan and Naomi were winding down a fortnight-long pilgrimage to India with a group of 25 members of the Synchronicity Foundation, a spiritual community in Central Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains that the family had been a part of for 11 years. The father and daughter were dining at the Oberoi when the terrorists struck.

“I knew that Alan and Naomi would not have wanted me to spend the rest of my life feeling sad, but I had to allow the sadness to envelope me before I could say enough is enough. The sadness was my personal winter and India provided the sunshine that brought some joy back into my life,” Scherr writes.

“As you go forth into your life each day, may you remember that love is ready to flow in abundance. We each hold this treasure. When we share our love, it increases and only then we know the highest value of life,” Scherr concludes.