Cover photo courtesy: http://www.oldcambrians.com/

BY MAHADEV DESAI

After earning his B.A.(Hons.) degree from Mumbai’s iconic Elphinstone College, my father taught in a secondary school in the same city and got married. In 1929, he, along with my mother and son (my elder brother) decided to move to Dar-es-Salaam, Tanganyika, East Africa’s largest city, for better opportunities.

Britain took over Tanganyika from the Germans in 1920. My father’s initial job was teaching at the Aga Khan High School. He played an active role in our Gujarati community and founded Surat District Association and also a literary society.

I, and my three other siblings were born in Dar-es-Salaam. I attended Arya Samaj Elementary school. I had an uneventful childhood. We went to the beach on Sundays. Some weekends, my dad took me to watch cricket matches between Indian teams. I do not have more memories of my early days in Dar-es-Salaam.

After about twelve years in Dar-es-Salaam, my dad took up a job in the Law Courts in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya. We traveled on ship to Kenya’s coastal town Mombasa and onto Nairobi by train.

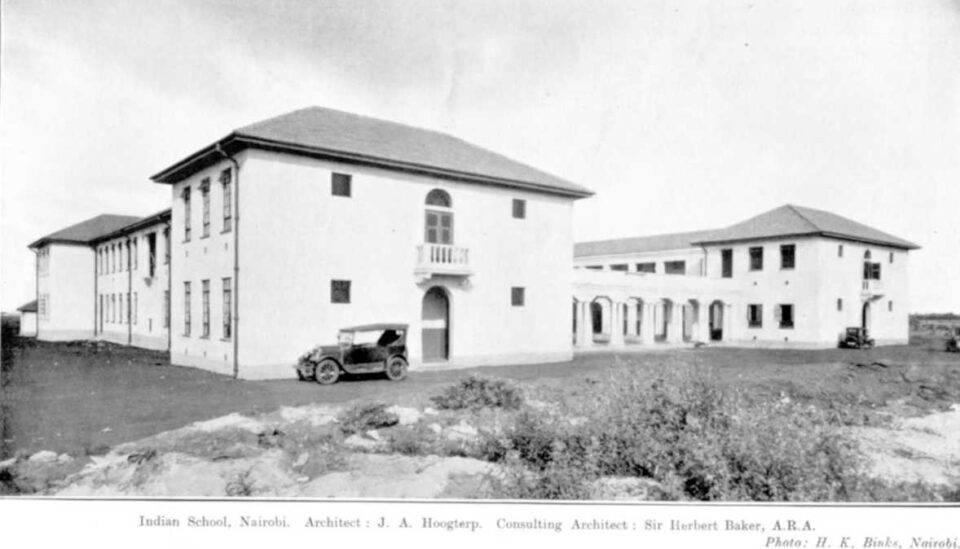

Nairobi, before Kenya’s independence on 12th December 1963, was less developed and bustling. Housing and education were segregated along racial lines with separate residential areas and schools for Europeans, Asians and Africans respectively. The white farmers, including Boers from South Africa, took over all of the fertile Highlands from the Africans and grew commercially rewarding crops like tea, coffee, cotton, wheat, sisal and pyrethrum. They virtually controlled the tourist industry, agriculture, transport, banking, and corporate sector. Indians were not allowed to own land in Kenya and Africans were permitted only subsistence farming. In Civil service, some of the departments like Immigration, Income tax, judiciary, etc. were run exclusively by whites.

Nairobi, a cosmopolitan city has Gujarati Hindus. A big majority are from close-knit Patel, Lohana and Shah Communities. Apart from Gujaratis, a small number comprises of Punjabi Hindus, Goans, Sikhs, Khoja Ismailis, and Bohras.

Indians dominated the wholesale and retail trade. They were very enterprising, hardworking, and resilient. They set up their petty shops (dukas) even into remote areas, where Africans could buy consumer goods imported from India, which they had never tried before. In Nairobi, they had a strong presence in the heart of the city. Those not in trade, performed clerical and middle-management position jobs in banks, civil service and corporations. The builders, saw-mill owners, motor transport operators and artisans-masons, carpenters, tailors, played a significant role in construction of the railway and forts along the coast and in overall development of the economy. They also imparted their skills and know-how to the Africans.

Shia Khoja Ismaili’s are followers of H.H.the Aga Khan. Nairobi has The Aga Khan University Hospital, Schools, Sports Club, etc. The community’s Khoja Mosque is a landmark building in the heart of Nairobi. The Ismailis have played a praiseworthy role in social and economic development of Kenya. The Shahs and Arya Samajis also have their schools. All these institutions play a useful role in providing education, health care and other services to the Kenyans.

My father began working in the Court and soon became eligible for accommodation in a two-room Government quarter. Most of our neighbors were Indian civil servants. My brothers and I walked to school and played with our neighbor’s children. A short period later, we moved to a three-room quarter and closer to our school. Our new home had an iron oven. We had to chop wood for this oven. For cooking my mother used charcoal. The latrine was in the backyard and night soil was collected by the municipal staff at night. The residential quarters were built close to each other in a circular shape, with a pear shaped, dusty ground in the middle. This dusty play ground was our favorite spot! Majority of schoolers from the quarters participated in traditional Indian games like gilli-danda, hu-tu-tu, marbles, etc. We also played cricket with improvised wooden bats and tennis balls. We also rode bicycles, climbed trees and swung from branches like Tarzans, stole fruits and flowers from neighbor’s gardens, and celebrated festivals like Holi with bonfires and colors. We included African kids in our teams and taught them various games being played. During winter months, we huddled together and roasted potatoes, and corn on charcoals. I cannot read or speak Swahili fluently but I picked up a few words like Jambo(hi); Habari gani (what’s the news); hakuna matata (no worries); Rafiki(friend); etc. through interaction with Africans.

Life was simple. We did not have a phone or a fridge or a car. My father had to travel with the Judges to Uganda, Tanzania, Aden, Seychelles, and Zanzibar and even to places in Kenya’s hinterland. He used to pen letters about any new place he visited. His letters were published under the heading, ‘Pravasi na patro’ (Letters from a traveler) in our community’s publication in India called ‘Anavil Pokar’ (Voice of Anavils.) He also gave talks on educational and literary topics to school kids, on ‘Voice of Kenya’ radio. When he retired as Registrar, he was bestowed with MBE for his long, exemplary services.

My brothers and I attended Government Indian High School, later renamed Duke of Gloucester School, which now is known as Jamhuri High School. The ‘all-boys’ School was modeled on a British school. We had to wear green blazers) and attend daily morning assemblies.

Most of our teachers were from India and Pakistan. The medium of instruction was English. Upon completion of High School, students sat for London Matriculation and Cambridge School Certificate examinations.

The school had sports grounds for cricket, soccer, field hockey and volley-ball. I was picked for the school’s cricket team. We played inter-school matches and matches against other cricket clubs. We looked forward to the annual Sports Day.

Cricket was very popular sport in Kenya. There were several Asian Cricket Clubs. Europeans also had their clubs. Inter-club Cup matches and the 3-day Asians v Europeans Test match, were keenly fought and aroused lot of passion among players as well as spectators and supporters. Cricket was played on matting wickets but later switched to turf pitches after Independence. Visits by Pakistan’s test players and teams from neighboring teams from Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia also drew large crowds.

Soccer is most popular sports in Kenya. It is also renowned for its long-distance runners. Besides sports, the other favorite pastime was cinema. Nairobi’s few cinemas screened both Bollywood and Hollywood movies. Drive-in cinema was also a popular haunt. On weekends, cars and vans filled to capacity with cinema fans and plenty of snacks headed there. We also enjoyed family and friends’ get-togethers during picnics near scenic waterfalls, or visits to Nairobi Arboretum and City Park.

Nairobi is known as ‘Safari Capital of the World’. Apart from the game reserves Tsavo National Park and Amboseli National Park, the coastal town of Mombasa is another tourist paradise with exotic beaches, palm trees, marine sports and luxurious resorts. For us, it was the preferred place for a holiday on the beach. Before the 1950s, Nairobi-Mombasa road covering a distance of about 325 miles was full of potholes and unsafe to drive. So, we chose to travel by train. The train ran on narrow-gauge tracks with a steam engine. From the train, we could see zebras, herds of impala, giraffes, and elephants grazing quietly, right near the railway tracks!

Kenya’s rich and organic soil produces delicious fruits and vegetables. We bought these from the market and shops but sometimes fresh juicy pears, plums and strawberries from hawkers on the outskirt of the city.

We celebrated all major popular Indian festivals like Holi, Diwali, Ganesh Chaturthi, Maha Shiva Ratri, etc., in our community halls, Temples or clubs.

Thread ceremony is one of the most important rites of passage in a Brahmin boy’s life. The ceremony is usually before a boy’s marriage. My father arranged thread ceremony of my six brothers and me in a go! I guess our family barber had to work overtime to give haircuts to us all!

My High School days were over. I passed both London Matriculation and Cambridge School Certificate examinations. There were no colleges in Kenya at the time, so I began preparing for my departure to Mumbai for a Degree in Business Studies!

What I have narrated above, is Kenya before independence. Readers are requested to read my two follow up articles:

My College Days in Bombay:

http://www.atlantadunia.com/Dunia/Features/F305.aspx and

My College Days in London: