By Vishnu Makhijani

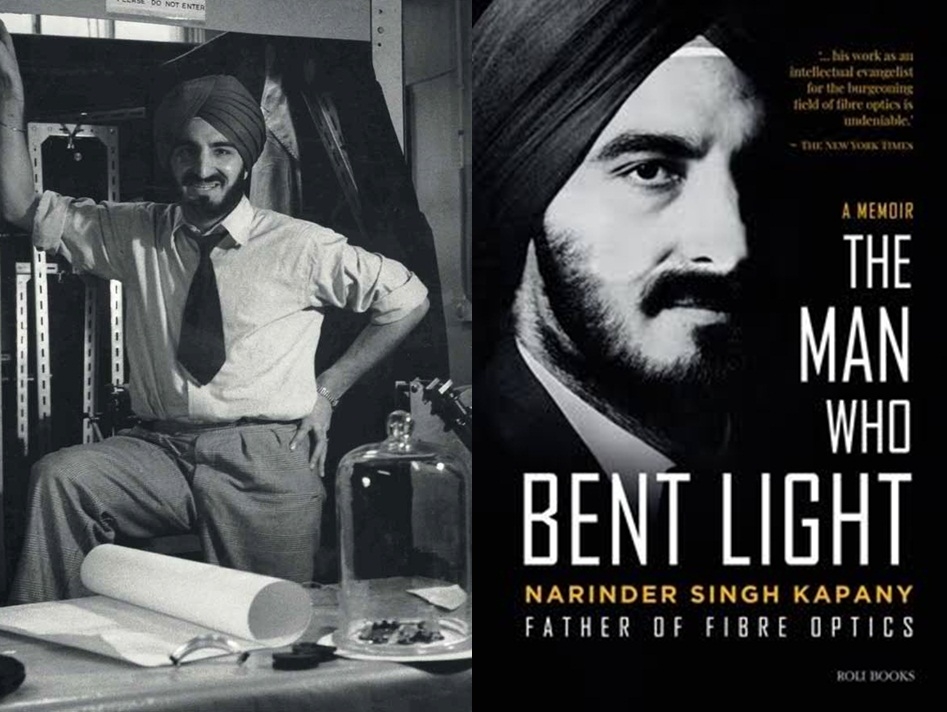

New Delhi, Jan 13 (IANS) He is considered the “Father of Fibre Optics”, one of the seven “Unsung Heroes of the 20th Century” for his Nobel Prize deserving breakthrough that spawned the Internet and is behind devices ranging from endoscopes to high-capacity telephone lines. Yet, the self-effacing Indian American Narinder Singh Kapany, born in the sleepy town of Moga in undivided Punjab devotes just two-and-a-half-pages in his 277-page memoir to this momentous achievement.

Instead, he focuses on his journey as an inventor-entrepreneur encompassing fibre optics communications, lasers, biomedical instrumentation, solar energy and pollution monitoring, registering in the process 120 patents, as also academics e but most importantly as a philanthropist.

Over the past 50 years, the Palo Alto, California, based Sikh Foundation that Kapany founded in 1967 pioneered the display of Sikh Arts at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It has worked tirelessly to promote and preserve Sikh art, heritage, education, culture, and religion by underwriting, mounting, and/or providing the art for numerous world-class Sikh art retrospectives, museum exhibitions and lecture series from London, to Toronto and the US, including New York City, Washington D.C. (at the Smithsonian for five years, Texas and California, where at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, Kapany donated the nation’s first permanent Sikh gallery.

All this is in addition to four Chairs that the Foundation has underwritten at the Universities of California Santa Cruz, Sana Barbara and Riverside and the California State University East Bay, as also its support for Punjabi language programmes at Columbia, Stanford and the University of California Berkeley.

“Together, we must work toward absolute equality for all, promoting love and charity. This not one way of moving forward; it is the only way,” Kapany, who died on December 4, 2020 aged 94, nine months after completing his memoirs, maintains in “The Man Who Bent Light” (Roli Books).

The spark was ignited in high school in Dehradun, where, a teacher told Kapany that light could travel only in a straight line. Determined to prove his teacher wrong, he went on to graduate from Agra University before going to Imperial College to work on a PhD in optics from the University of London.

In 1953, working alongside physicist Harold Hopkins at the Imperial College, Kapany, after a great deal of trial and effort, was the first to successfully transmit high-quality images through fibre bundles, coining the term fibre optics in a 1960 article for Scientific American.

He describes the breakthrough rather modestly:

“On my request, Professor Hopkins appeared in the lab… I (had) affixed a black mask with the cut-out word eFIBRE’ to a lens that I had set up in front of the business end of the remaining end remaining (optical glass) bunch and beamed it to a makeshift projection screen on the far wall.

“Well, Kapany, what do you have to show me?

“I pulled up the single chair in the lab, placed it with the best sight line to the screen, and urged him to sit.

“Ready, I asked.

“Yes, yes, he said, feigning impatience.

“I closed the door, shut off all the lights, and in a single, final effort, I switched on the light source. And there it was. On the screen. Like an optometrist’s chart but with only a single line of large letters, as clear as it could be: F…I…B…R…E.”

Kapany had proved that ultimately, what it comes down to is persistence.

“Doggedness is an important attribute in a field where, by most measures, only a fraction succeed,” Kapany writes.

This was an attribute that followed him through his life.

In 1961, Kapany along with his wife moved to Woodside on the San Francisco Peninsula and today one of the wealthiest communities in the US, where he founded Optics Technology Inc. successfully taking it public in 1967. He was the first Sikh Indian to take a company public in Silicon Valley. The San Francisco Examiner, in February 1969, described him as eethe most dashing corporate officer in the area’. Subsequently, he founded Kaptron Inc. in 1973, which was later acquired by AMP Inc.

In between, he was offered the post of Scientific Advisor to then Defence Minister V.K. Krishna, with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru himself forwarding the recommendation to the UPSC, which made such senior appointments. However, the offer was a year in coming, during which Kapany had moved on.

He was later offered the position of Assistant Secretary for Commerce in the administration of Richard Nixon but this didn’t go through as he was known to be uncomfortable with the then US President.

Kapany even had an extended meeting with Daniel Patrick Moynihan when he was named the US Ambassador to India to come on board as his number two

“It was not to be the case, however, and largely, I believe, for the very trepidations he had expressed in our conversation that day: that it was simply too early in modern India’s development for a partnership such as ours,” Kapany writes.

It’s a measure of the man who was posthumously awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second-highest civilian award, that he has no regrets.

“To the years gone by, I bid a fond farewell. For those yet to come, I welcome them, I embrace them,” Kapany wrote in the concluding chapter, titled “In Closing” that he signed off in March 2020.