BY JYOTHSNA HEGDE

“Not since Buddha has India so revered any man. Not since St. Francis of Assissi has any life known to history been so marked by gentleness, disinterestedness, simplicity of soul and forgiveness of enemies. We have the astonishing phenomenon of a revolution led by a saint,” Will Durant, American historian best known for The Story of Civilization, said about the Mahatma. With homages and tributes from historians, philosophers and even scientists such as Einstein, the journey of Gandhi’s elevation to Mahatma, in itself, offers an exhaustive line of study.

Hailed by London Times as “the most influential figure India has produced for generations” upon his passing, Gandhi’s enduring legacy remains fresh and thought-provoking to this day, including his emphasis on the importance of facing up to the truth with courage. Who and what influenced the influencer of the world?

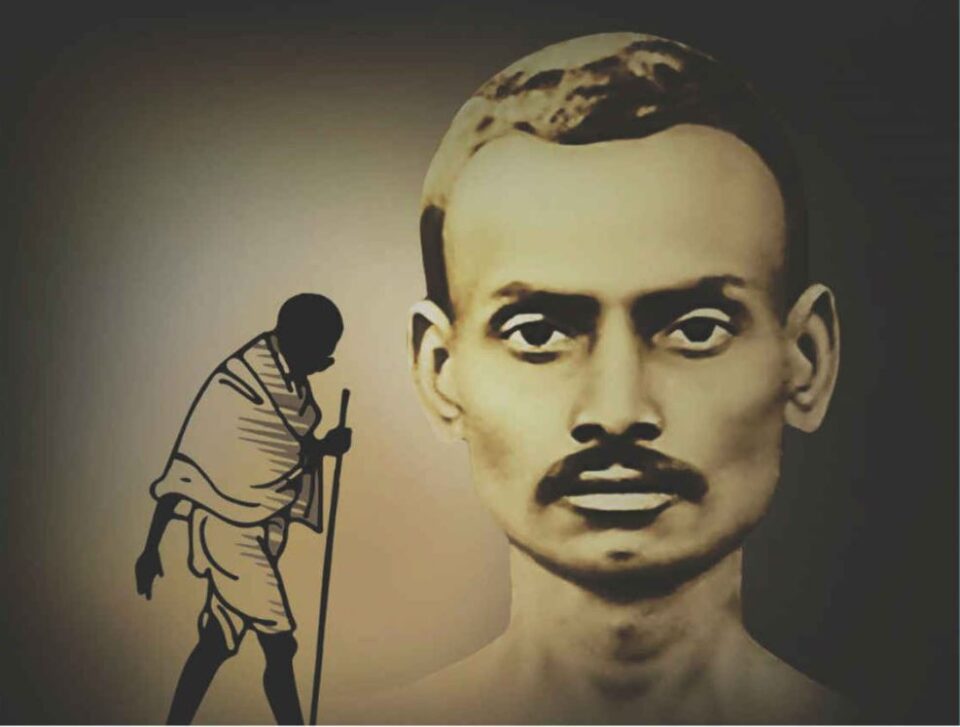

In Gandhi and Rajchandra: The Making of the Mahatma. (Lexington Books), Dr. Uma Majmudar walks the reader through the life and times of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, exploring his transformation through various influences in his life, Srimad Rajchandra in particular. Through her comprehensive research and analysis, she convincingly presents the profound impact of a Jain zaveri (jeweler)-cum-spiritual seeker upon Gandhi, who “molded Gandhi’s inner self, his character, his life, thoughts and actions.”

With specialization in Gandhian philosophy of peace and nonviolence, and having authored her first book also on Gandhi, Dr. Majmudar, in her second book, draws deeply from wisdom of Jain traditions and Shrimad Rajchandra and the lasting impressions they imprinted on the Mahatma, with detailed accounting of their initial meeting, their interminable connection, reflective relationship, profound discussions and their philosophical correspondence. As Dr. Majmudar puts it, “What Shri Krishna was to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, Rajchandra was to Gandhi — a trusted friend, a ‘soulmate,’ and a spiritual mentor-adviser-teacher as well!”

On the very first day of his return from London in 1891, the twenty-two-year-old Barrister-at-law—Mohandas Gandhi, was introduced to Rajchandra, barely two years older than Gandhi, as a ‘kavi’ (poet). But before Gandhi could explore his spiritual side, Dr. Majmudar notes, Gandhi was introduced to Rajchandra as a “shatavadhani,” meaning, one who can remember a hundred things at a time and reproduce them precisely in the same order as presented to him. The poet could also engage in many different activities simultaneously (e.g. counting money, playing cards, composing poems instantaneously) without ever failing. In offering a word-memory test, the western-educated young barrister presented his newly acquired European words, only to have them repeated in the precise order he received them. “I was impressed, but not inspired, “Gandhi had said later.

In the time that Gandhi spent in close contact with Rajchandra, he observed and studied him, listening to his discourses, questioning him, and engaging in deep philosophical-spiritual conversations with him, writes Dr. Majmudar. “He even aspired to be like this spiritual gem, who in the midst of ‘samsara’ (world), remained “jala-kamala-vat” (jala: water; kamala: lotus, and vat: like) or as “unattached as a lotus floating on the surface of water!”

Amidst heterogeneous influences of cultures and religions, especially through his travels and sojourns of various countries, Gandhi faced a spiritual crisis, especially during his trip to South Africa, feeling burdened by clash of faiths. Gandhi wrote about his dilemma to Rajchandra whom he mentions as Raychandbhai in his autobiography, The Story Of My Experiments with Truth. Gandhi sent him 27 questions, and the answers that came back helped Gandhi resolve his doubts and restore his faith in Hinduism. The success and highlight of Dr. Majmudar’s book lies in its illuminance of the fact that despite his various conflicts in his eternal pursuit of truth, Gandhi’s eventual self-realization was rooted in his own tradition and culture. Dr. Majmudar successfully builds and binds the relationship of Gandhi and Rajchandra, highlighting their various conversations and Gandhi’s own references that guided him during his time of religious and ethical crisis. In Gandhi words: “I have met many a religious leader or teacher… and I must say that no one else ever made on me the impression that Raychandbhai did.”

“Their relationship evolved from being soulmates to becoming close friends and seekers of truth, culminating into that of the teacher and the taught,” writes Dr. Majmudar. As psychoanalyst Erik Erikson in his study of Gandhi noted and the author cites, “Rajchandra was the first spiritual anchor of young Gandhi’s religious imagination during the very period of his life where he felt most lost.”

The book also highlights attributes of Gandhi’s unwavering acceptance of all religions to the influence of Rajchandra. “That Gandhi was profoundly influenced by Rajchandra’s humanistic and latitudinal approach to religion will be evident in how he would later define it in “All men are Brothers” Religion is that which underlies all religions, and which brings us face-to-face with our Maker. Gandhi’s attitude of equal respect toward all religions (“sarva dharma sama bhava” in Sanskrit) underscores a direct, profound influence of Srimad Rajchandra.”

Designating Gandhian Satyaraha as the finest fruit of Rajchandra’s teaching, Dr. Majmudar describes the formation of Gandhi’s extraordinary principle of Satyagraha, writing, “… even after the poet’s (Rajchandra) early demise Gandhi would continue to follow in his mentor’s footsteps and translate his principles of truth, nonviolence and acetic self- control into his mass-scale satyagraha.” Citing Rajchandra’s views and advocacy of women’s education and reform, the author states that Gandhi adopted this practice later during his satyagrahas.

The book also sheds lights on Gandhi’s general outlook on women as influenced by Rajchandra, describing him as “role-model” for Gandhi in regarding women neither as sex-objects, nor as an impediment to a higher spiritual sadhana. As the author notes, “Both opposed child- marriages, ill-fitted marriages, and other social discriminations against women. Both emphasized women’s enormous “shakti” or “power”— their intrinsic moral and spiritual potential for forbearance and forgiveness, their ability to suffer but not yield to any injustice.”

One of the highly debated aspects of Gandhi’s lifestyle choices, his views on practice of celibacy or “brahmacharya,” especially about practicing it in marriage, as the book underlines and Gandhi acknowledges in his autobiography is ascribed to Rajchandra. “I cannot definitely say what circumstance or what book it was, that set my thoughts in that direction, but I have a recollection that the predominant factor was the influence of Raychandbhai.” Of all the “moral-spiritual” lessons that Gandhi learned from Rajchandra, Dr. Majmudar states celibacy featured at the top of the list. In her words, “….brahmacharya (next to ahimsa ), was the second most important principle which he (Gandhi) earnestly embraced early on in his life and pursued all the more rigorously toward the end.”

The books also touches upon other principles Gandhi abided by, such as vegetarianism, palate control, dietic experiments, sexuality, also impacted by Rajchandra.

Dwelling deep into their relationship, Dr. Majmudar provides an absorbing, and expansive evaluation of the evolution of Gandhi’s connection with his mentor and his metamorphosis into “Mahatma”, summing up her compelling narrative with “If Mohandas Gandhi evolved into a ‘Mahatma”, who else but Shrimad Rajchandra would he gratefully acknowledge for the “Making of the Mahatma!”

For someone who passed away at the young age of 33, Rajchandra surely etched an everlasting impression on the Mahatma, who furthered his vision that continues to remain relevant to this day, and beyond borders. A fine testament to the revolutionary power of Satyagraha (the force that is generated through adherence to Truth), Gandhi’s approach reached our city of Atlanta, directly influencing Martin Luther King, Jr., who argued that the Gandhian philosophy was “the only morally and practically sound method open to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.”

Dr. Majmudar’s earnest efforts in highlighting this exceptional bond only enhances and elevates an evergreen, ever-relevant study of the Mahatma and his principles.

About the Author:Dr. Uma Majmudar teaches in the philosophy and religion department at Spelman College. A native of India, she emigrated to the U.S. with her family in 1967. With a zest for higher learning, writing and public speaking, Uma earned her Ph.D. from Emory University in 1996. Specializing in the Gandhian philosophy of peace and nonviolence. Uma Majmudar authored her first book: “Gandhi’s Pilgrimage of Faith: From Darkness to Light” (SUNY, 2005).