By Vikas Datta

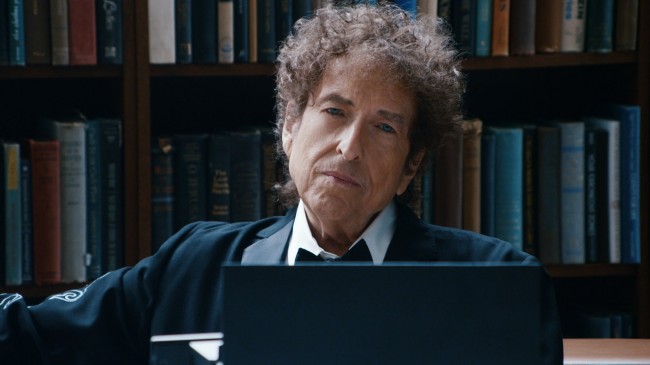

Choosing Bob Dylan as the recipient of this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature was unprecedented in the award’s over-a-century-long history. While the Swedish Academy’s decision to select a songwriter, instead of a writer or poet, has earned much praise — and much criticism too — its real significance lies in what it means for the definition of literature, and the unnecessary distinction between high and popular culture.

On social media itself, there have been many who welcomed the award for an abiding musical legend, whose self-written lyrics have been eloquent anthems of iconoclastic protest against stultifying tradition, inequitable status quo and conformity. On the other hand, many disparaged the decision, saying he is “no writer”, mentioned “all the great literary works that are lying around, waiting their due credit”, and even that he is a “university dropout”.

Some of the objections seems dubious and self-centred. Is literature only the product of a writer or a poet or a dramatist, and then who is an author anyway? Is it someone who thinks he/she is an author, or someone who is called an author, or someone whose works are known? And then why an educational qualification — are authors only those with a degree in literature or a diploma in creative writing?

What about the other “great literary works”? The Nobel, like many other awards, has never been free from controversy. Many scientists, especially women like Lise Meitner (worked with Otto Hahn on nuclear fission) and Rosalind Watson (made a seminal contribution to Frances Crick and James Watson’s double helix model of DNA) were left out, while their male counterparts were honoured. President Barack Obama won the Peace Prize at the beginning of his stint unlike other recipients who had to do something for it.

Leo Tolstoy, Henrik Ibsen, Mark Twain, Franz Kafka, Anton Chekhov, Graham Greene, Vladimir Nabokov, Jorge Luis Borges, Faiz Ahmed Faiz and so on never received the Nobel Prize. Criticism greeted the selection of so many European authors not known outside their own countries, and even of John Steinbeck — The New York Times said his “limited talent is, in his best books, watered down by tenth-rate philosophising”.

And then to literature itself. Is the oral tradition not literature, or does it have to be printed in book form to deserve the name? Many seminal works — religious epics, creation sagas, fairy tales and fables, poems and so on existed long before they were reduced to a tangible printed form, studied by researchers and prescribed in syllabi. Were they literature then, or are they now?

Take some concrete examples. Compare “If you’re traveling the north country fair/Where the winds hit heavy on the borderline/Remember me to one who lives there/For she once was a true love of mine” with “Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet;/She passed the salley gardens with little snow-white feet./She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow on the tree;/But I, being young and foolish, with her would not agree”.

Even these two vividly surreal scenarios: “Down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves/The haunted, frightened trees, out to the windy beach/Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow” with “Let us go then, you and I,/When the evening is spread out against the sky/Like a patient etherized upon a table.”

The first verse in both cases is Dylan and the second writers are William Butler Yeats (Nobel Prize for Literature, 1923) and T.S. Eliot (Nobel Prize for Literature, 1948), respectively.

In an article for the Smithsonian Institute’s online magazine, American historian David C. Ward notes that while Dylan’s lyrics can stand alone as poetry “in terms of the tradition of free verse in the 20th-century”, this was “a criterion that will not satisfy many”. However, since Dylan “turned words into music, many of his lyrics are more traditional in the way that they rhyme and scan than critics might admit”.

Ultimately, it is about personal choice. How many of us have read Mikhail Sholokhov, Selma Lagerlof, Jacinto Benavente, or Yasunari Kawabata because they are Nobel laureates?

And then what is the big deal about a Nobel, as many, including the likes of Karel Capek and Jean Paul Sartre, have asked?