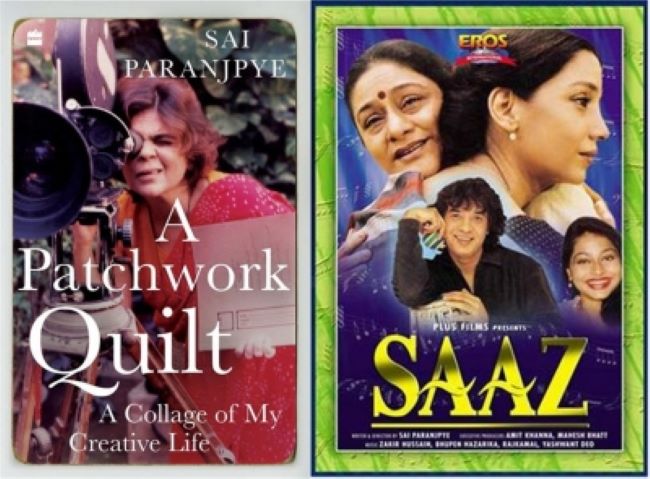

BY SAI PARANJPYE

The film on Asha Bhosle’s life was cancelled and we decided to make a work of fiction about imaginary people. We did (in Saaz), however, stick to the idea of there being two sisters, both endowed with heavenly voices.

I have always mulled over sibling syndrome, especially with regard to the Mangeshkar sisters. Attached to each other as they are by close-knit bonds of love, how do they handle the predicament when they are poised at the crossroads as opponents? How does the conflict between a blood bond and professional rivalry get sorted out?

I decided to transfer this perplexity of mine to the screen.

I would like to mention here that though the story of the two sisters of our film was purely fictional, I did use two select incidents from real life in the narrative. Both are very much in the public domain, so I did not disclose any guarded secrets.

The first incident was narrated by Vishram Bedekar in his autobiography, ‘Ek Jhad Don Pakshi’. Master Dinanath, the father of Lata and Asha, had an alcohol addiction. Late one night he arrived at Bedekar’s doorstep to borrow a little money to quench his thirst. It was a stormy night and the heavens were raging, unleashing torrents of rain.

Bedekar reprimanded the artiste saying, “It does not behove a great talent like you to seek charity at someone’s door on a night like this.” Stung, Dinanath began to sing, getting wholly drenched as he did so. He sang as never before and then, collecting the amount he had rightfully earned, marched off triumphantly.

To my mind, this scene is one of the highlights of ‘Saaz’. The other episode I have used in the film is that of Lata singing the patriotic song, ‘Ae mere watan ke logon’, instead of Asha, at a high-powered function in Delhi.

Apart from these two incidents, everything in ‘Saaz’ is fictional. It is no one’s biography, only an imaginary tale.

Once I had decided on the modus operandi, writing the film was an easy task. Scenes seemed to unravel on their own, each with its own identity. Every twist and turn, every romantic involvement, every dialogue was my own invention. To give a few examples of the disconnect between the film and reality, I can cite, for one, the early death of the girls’ mother.

Mai, the real mother of the Mangeshkar sisters, happily lived to a ripe old age and was able to see the glorious achievements of her daughters in her lifetime.

Then again, both Mansi and Bansi in the film have an emotional attachment to the same man (a departure) and Mansi leaves the world well before her time (may Lataji live a hundred years). Bansi’s daughter falls in love with a young music director, Himan, who is in fact infatuated with her mother.

He tragically dies in an accident and the shock makes Bansi lose her voice. Keeping these fictitious happenings in mind, how can anyone claim that Saaz mirrors the life story of the sibling nightingales?

But no matter how earnestly I pleaded my case, the indelible blot could not be wiped out. Two sisters, and both playback singers — that was basis enough for people to draw their own conclusions.

I faced a lot of flak over ‘Saaz’. The admirers of the sisters, especially Lata’s fans, were aggrieved with me. On my part, I never disowned the fact that the original idea — only the idea — was indeed inspired by them.

(Excerpted from ‘A Patchwork Quilt — A Collage of My Creative Life’ by Sai Paranjpye with the permission of the publisher, HarperCollins India)