BY VIKAS DATTA

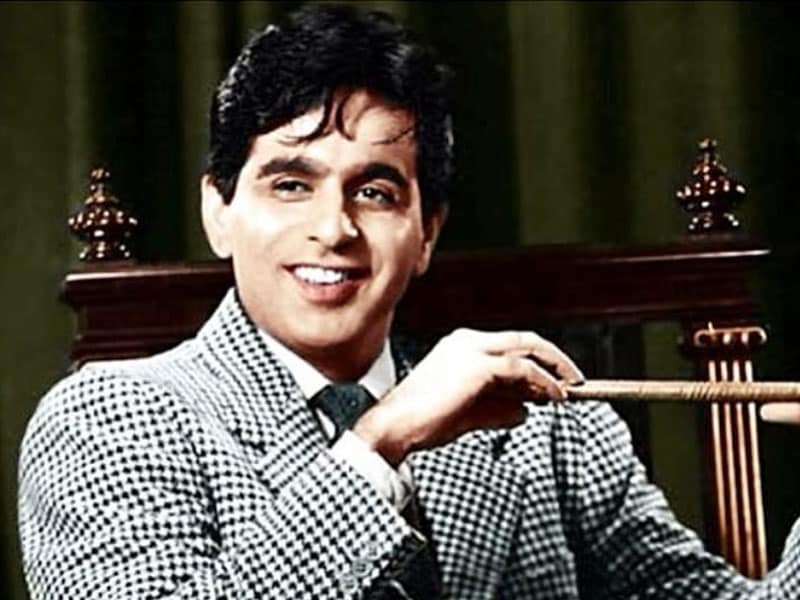

Debuting on screen in British India, appearing in some of Indian cinema’s greatest classics and present in the hearts of a vast multitude of fans for over eight decades, Dilip Kumar was not just Bollywood’s oldest living star but also an Indian institution.

The “Tragedy King” who excelled in broad comedy too, could play a prince or a peasant, a betrayed lover or a stern patriarch or with equal ease, display profound intensity or a jaunty nonchalance with the same skill, Dilip Kumar, who passed away on Wednesday, repeatedly reinvented himself as both an actor and a person.

“Taqdeeren badal jaati hai, zamana badal jata hai, mulkon ki tareekh badal jaati hai, Shahenshah badal jaate hai, magar is badalti huyi duniya mein mohabbat jis insaan ka daman thaam leti hai, wohi insaan nahi badalta…” he said, as Prince Salim in one of his most memorable roles. And this might describe Dilip Kumar’s own long, inspiring life but not his acting.

For just over two decades later after masterfully playing the rebellious son facing-off a stern and dutiful father in “Mughal-e-Azam” (1960), he could take on the latter role in “Shakti” (1980) with same intensity, though not the bombast of Prithviraj Kapoor.

That was the calibre of Mohammed Yousuf Khan, alias Dilip Kumar, a natural actor using the “method system” before it was even named in a career lasting over half a century.

A Pathan boy who got personally picked by then Bollywood reigning diva Devika Rani to debut opposite her in “Jwar Bhata” (1944), he went on to become the tragedy face of Bollywood’s first trinity – where he outlived and – arguably outperformed – Raj Kapoor’s naivety and Dev Anand’s cheerful insouciance. All subsequent superstars from Amitabh Bachchan to Shah Rukh Khan would owe him a debt.

But there was more to his career than we know.

For one, of the “shy 22-year-old son of a Pathan fruit merchant”, born and raised in Peshawar, played a Muslim in only one of his 60-odd films — in “Mughal-e-Azam”, while the Abdul Rahim Khan of “Azaad”, 1955, was a guise for Kumar alias Azaad, and was more likely to be named Shankar (or Ram and Shyam, or Vijay or Kundan).

Above all, he “single-handedly refined histrionics” and refining acting “to an art form of exalted brilliance”, says his wife Saira Banu in her introduction to his memoirs “Dilip Kumar: The Substance and the Shadow”.

And this was despite having no plans of joining the profession but believed – by his grandmother especially – to be destined for fame, following a faqir’s prediction. Then his father Ghulam Sarwar’s decision in the 1930s to shift his business and family near then Bombay in the late 1930s and his own independent streak, all in their way, led to Yousuf Khan becoming Dilip Kumar.

Far too many remember him for his “brooding” roles. But while he performed these with a restrained and refined subtlety, from the fatal modern triangle of “Andaz” (1949) to the pre-modern “Devdas” (1955) or even “Yahudi” (1957) set in Ancient Rome, down to “Mashaal” (1984) and “Karma” (1986) respectively, he had a much-varied palette.

If he could play the lovelorn Prince Salim, he could also be the bouncy and swashbuckling Jai Tilak of “Aan” or more outgoing Yuvraj in “Kohinoor”, match portrayals of the rustic Gungaram of “Ganga Jamuna” (1961) or Sagina Mahto (in both the eponymous Bengali film and its Bollywood remake) with those of city slickers like ebullient prankster Vijay Khanna of “Leader” (1964) or the rich, spoiled twin Sanjay in “Bairaag”.

But, Dilip Kumar also symbolised newly-independent India in all its diversity and promise of a bright future, showcased in films like “Naya Daur” (1957), as Lord Meghnad Desai argues in “Nehru’s Hero: Dilip Kumar in the Life of India” (2004), but also his personal life.

While Saira Banu relates her husband could give a mellifluous azaan or quote from the Quran, but also from the Bhagvad Gita and the Bible, celebrates Diwali with the same fervour as Eid, he had also, as Sheriff of Bombay in the 1980s, presided over the breaking of the arduous 30-day fast of Jain children.

And he had no airs. My father Vijay Datta, who worked for liquor company Mohan Meakins, recalls as Dilip Kumar, as a director, was a frequent visitor to the plan at Ghaziabad, Solan and Lucknow, where would cheerfully interact with all in chaste Urdu or “theth” Punjabi and was remarkably self-effacing.

It has been a ‘Suhana Safar’ for Dilip sahab.