BY JYOTHSNA HEGDE*

A circle of men sit huddled under a flickering bulb, their shadows clinging to peeling walls, the air heavy with incense smoke from a funeral earlier that day. In the center, Ravi Anna—the village’s unspoken chieftain, played with magnetic ease by Shaneel Gautham—leans forward, voice dropping to a conspiratorial hush as he spins a ghost story. His loyal entourage hangs on every word, though one keeps interrupting, chanting like a warding mantra: “If you get scared when you meet the demon, you’re done.”

Then—a sound, sudden and sharp—splits the silence. Chairs scrape, eyes widen, fear prickles the skin… until the source is revealed as nothing at all. Nervous laughter spills into the humid night, part relief, part sheepishness. In that moment, Su From So shows its hand: fear and folly, courage and comedy, all bound in the close-knit rhythms of a coastal village.

From here, Su From So unfolds with the languid confidence of a storyteller who knows his people well. JP Thuminad—writer, director, and lead actor—roots his debut in the sun-washed, rain-slicked world of Mangalore’s coastal hamlets where superstition strolls alongside reason, rumor races the monsoon wind, and eccentricities swell into legend.

The story begins with a jumpscare and a sudden death, followed by elaborate mourning rituals and a communal feast. The director uses this opening not just to set the tone but to draw us into the fabric of the village itself.

The central tension arrives quietly: Ashoka, a carefree young man, becomes the subject of a bizarre rumor—that he’s possessed by the spirit of a woman named Sulochana. Ashoka’s “haunting” by Sulochana—a stoic older woman from the neighboring village of Someshwara (Su from So)—becomes an anchor for both eerie humor and a sly nod to local folklore.

What begins as a comic misunderstanding spirals into village-wide hysteria, pulling in an ensemble of characters so vividly drawn that they feel like people you’ve met in a bustling market or at a coastal tea stall.

The villagers, armed with tradition, half-remembered rituals, and absolute conviction, band together to drive the ghost away. In the background of this supposed haunting, the film gently explores the bonds, tensions, and everyday rhythms of community living—the way people close ranks in times of trouble, and the warmth that underpins even the most outrageous rumors.

What could have been a conventional horror tale becomes, in Thuminad’s hands, a satirical comedy—without cruelty. Thuminad doesn’t mock his characters; instead, he invites us to laugh with them, to see their quirks and contradictions as reflections of our own. The local dialect is as much a star as any actor, its turns of phrase and quicksilver rhythms transforming everyday banter into moments of charm.

The world of Su From So is a quaint village in Dakshina Kannada—a tight-knit community where joy and sorrow are shared with equal fervor. The village itself is a living ensemble, each character a thread in the fabric.

Ravi Anna’s authority is equal parts charisma and performance; his courage sometimes wavers when no one is looking. By his side is Sathish Anna (Deepak Rai Panaje), ever-loyal and ready to back up his leader’s pronouncements without question. Rickshaw Chandra Anna (Prakash Thuminad) carries gossip as deftly as passengers. Yadhu Anna (Mime Ramadas) forms committees for anything and everything, delighting in speeches that trail into tangents. Ramesh Anna (Pushparaj Bolar) and his family, including his son Ashoka, stand at the heart of the ghostly crisis. Bhanu (Sandhya Arekere) offers quiet resilience amid the chaos.

Every corner of the frame breathes life, from a child peering from behind a pillar to a fishing boat rocking gently as the community debates the spirit world. Inhabitants of this space, be it the nearly blind elder who still catches every scrap of gossip, the perpetually tipsy Bava (Vijay Kumar), game for any “mission” that involves liquor, the youth obsessed with his crisply ironed shirt, or the impossibly skinny woman with an appetite that defies science. These people don’t just populate the village—they make it pulse with life.

The performances are lived-in and unshowy. Shaneel Gautham’s Ravi Anna radiates the easy authority of a man who knows his place in the social order—yet allows flickers of vulnerability to break through. While he projects the confidence of a leader—chest puffed, voice steady—there’s susceptibility under the surface. His storytelling bravado in that drinking scene is the armor he wears, but when confronted with genuine uncertainty, his eyes betray flickers of fear.

The performance by Shaneel Gautham ensures Ravi Anna remains both relatable and human. He’s not a caricature but a man trying to hold his ground, even when he’s unsure what that ground really is.

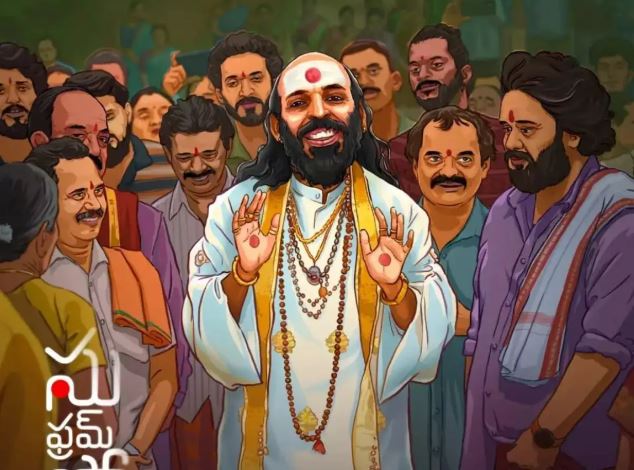

And then there’s Raj B Shetty—not just producer but creative anchor—who, under his Lighter Buddha Films banner, resisted selling the movie on his own name and instead let its rooted narrative stand tall, keeping his role a secret until release, when he appears as Guruji, an eccentric, slightly effeminate exorcist with a flair for the theatrical.

He plays the role with a knowing, playful touch that skewers self-styled holy men while blending seamlessly into the village fabric. His off-screen influence is visible in the film’s authenticity, its unhurried rhythm, and its embrace of new talent.

JP Thuminad gives Ashoka the bewildered energy of someone caught between the mundane and the inexplicable. He is the perfect catalyst for chaos. Whether or not he’s truly possessed is almost beside the point; what matters is the way the village responds. Some are quick to offer solutions steeped in ritual, others gossip from the sidelines, and a few—like Bhanu (Sandhya Arekere)—become collateral damage in the mess.

Midway through, the narrative shifts. Beneath the laughs lies Bhanu’s story, played with quiet power by Sandhya Arekere.

Without warning, the lightness of the earlier scenes gives way to something more layered. Through Bhanu, the film addresses the unspoken social constraints faced by women in communities. Her struggles are never presented with melodrama, yet the emotional weight is undeniable.

It’s a tonal pivot that works because the groundwork has been so carefully laid; we’ve already invested in these people, so when the mood changes, it feels earned.

The film doesn’t shy away from showing how the recklessness of men can ripple out and affect women disproportionately. Yet it never turns preachy. The point is made subtly, embedded within humor and human interaction.

As the “haunting” progresses, the line between reality and belief grows softer. The villagers, anchored in old customs, interpret every odd occurrence as proof of Sulochana’s presence. Fear becomes its own storyteller, weaving coincidences into fate.

And through it all, the camera watches without judgment, catching fleeting details. The editing allows space for silences and sidelong glances, embracing the rhythm of rural life rather than forcing urgency. Each frame feels lived-in, authentic, and unvarnished.

If there is a minor indulgence, it’s in the pacing. Some scenes stretch like the hot, slow afternoons they depict, the narrative occasionally meandering. Yet this unhurriedness feels deliberate—a refusal to rush through the relationships, rituals, and conversations that define Su From So.

The humor emerges organically—sometimes broad, sometimes sly. A ritual misfires because someone forgot the right kind of incense. A heated debate on ghost-banishing devolves into an argument over committee meeting minutes. Even moments meant to be solemn are laced with absurdity, as when a villager insists the “signs” point to Sulochana’s displeasure simply because his coconut tree hasn’t borne fruit this season.

In the end, Su From So is less a ghost story than a story about the people who tell them. It’s the kind of tale shared on verandahs during power cuts, where reality and fiction mingle and the pleasure lies in the telling as much as in the truth.

Rustic, affectionate, and brimming with local flavor, Thuminad’s debut captures a community in all its warmth, stubbornness, and eccentricity—reminding us that sometimes, the most haunting thing of all is how deeply we belong to the places and people we call our own.

*Jyothsna Hegde is the City News Editor of NRI Pulse.