BY JYOTHSNA HEGDE

On June 19, 1982, Vincent Chin, a Chinese American was at a strip club in Detroit with his friends celebrating his upcoming wedding. These were times when Michigan, once known as an automotive manufacturing capital, was in decline. Many U.S. autoworkers blamed this decline on Japanese car manufacturers. That night, two white men who apparently thought Chin was Japanese, beat him to death. At the killers’ trial, the men each received a $3,000 fine and zero prison time. Eight-year-old Anjali Enjeti, who lived with her family a few miles away, tried to process this information as best as she could – “If the killers didn’t care that Vincent is not actually Japanese, they probably won’t care that my Indian dad is not Japanese, either… Who is safe? Who is not safe?” she wondered, worried. Little did she know that the injustice of it all would eventually pave the way for an activist life she would build for herself.

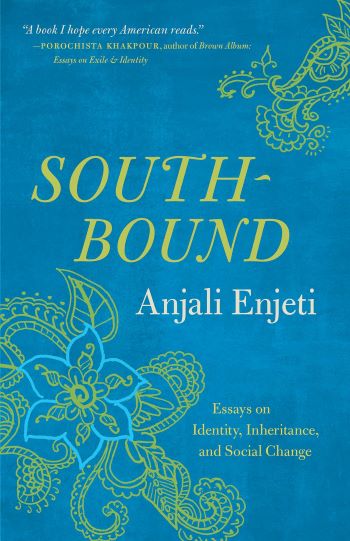

“The art of writing is the art of discovering what you believe,” is an astute perspective articulated by author Gustav Flaubert. A fine example of the quote, Anjali Enjeti’s Southbound, written amidst an unprecedented pandemic across the globe and the rise of the BLM movement in the US, reflects the author’s own complex life experiences and evolving ideas about identity, race, social justice, feminism, nationalism, and the ways it formed the activist, journalist, and author that she is today.

In her potent opening, “What are you?” a question that she describes, has been absorbed by the tympanic membranes of her eardrums and traveled through the synapses of her brain and followed her for decades since the day her family moved from Michigan to Chattanooga, Tennessee, Enjeti highlights her tumultuous experiences as the only brown student at school. Made to feel “abnormal and abhorrent” for not being easily identified within any race bracket, Enjeti elucidates her instincts for survival that were inclined toward conforming to and adulating whiteness that surrounded her or submit to silence or complicity.

“I am half Indian, a quarter Puerto Rican, and a quarter Austrian. I am an immigrant’s daughter and a daughter of the Deep South. Despite an ever-increasingly diverse United States, I remain a perpetual foreigner,” she writes. However, as the chronicles progress, we learn about the way Enjeti, who regrets a few of her complacencies, such as her silence when a fellow intern at the National Organization for Women was fired for voicing her convictions to a lawmaker, and angered by the injustice inflicted on people of color, identifies herself as part of the problem of racism in the South, and transforms her feelings of hurt and anger into meaningful action – through her fruitful work in getting Asian Americans in record numbers to the polls and turning Georgia blue in the 2021 elections, through They See Blue, which she co-founded in 2019.

Poignant and sincere, Enjeti writes about her own morphing views about feminism and abortion over time. Traversing along timelines, Enjeti weaves her heartbreaking miscarriages alongside experiences of her Austrian grandmother, Oma’s struggles with multiple pregnancies post four children. “I have evolved from the college student who feigned empathy for another woman’s dilemma on the Mall in Washington, D.C., the textbook feminist with the good fortune to view life in black and white, into a mother armed with hindsight and history— both mine and Oma’s—who now knows what it might be like to regret conception, to confront despair, to grieve the lack of second chances, to become pregnant with a baby I would have loved but never would have birthed.”

Enjeti delves into the early years of the AIDS epidemic in the South, zooming into the misconceptions shrouding the disease and the resulting mistreatment of patients. “Activism takes many forms,” writes Enjeti, about her physician dad, who, despite enduring discrimination himself, championed for the cause of gay AIDS patients. “This is how he [her dad] unknowingly modeled activism to me.”

The journalist in Enjeti shines through in her reporting on activists supporting Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees.

Critiquing

the “whiteness of southern literature”, Enjeti cites classics such as To

Kill a Mockingbird and A Time to Kill, which, she observes “fetishize

Black pain to redeem white characters.” Enjeti highlights the resulting

consequences that feed a false sense of being less racist by the mere act of

reading these books.

Collating her experiences over ways in which racism manifests in subtle and

elusive forms, Enjeti observes that engrained hatred in many ways is far more

hazardous as people remain in collective denial. “The most dangerous form of

extremism is like a train approaching in a thick fog. You can’t see it until

it’s about to run you over.”

“We know exactly how to make our country safer, but too many Republican legislators offer only “thoughts and prayers” instead of supporting meaningful legislation,” writes Enjeti about gun violence. Her fear for her own kids’ safety and well as the generation is palpable.

Placing responsibility on consumers of the news to demand better decision-making from media outlets, Enjeti underlines the importance of separating truth from objectivity. The assumption that news is neutral, “is as mythical as a unicorn. It exists only in the imagination,” she notes.

Her Chai and Chaat sessions to mobilize AAPI voters, inspired by the Tea Party movement and “Armchair” activism, such as a tweet that can lead to tangible outcomes in something as important as voting rights are fine examples of Enjeti’s indomitable activist spirit that will try anything for the cause she believes in. Her comprehensions, based on her own experiences, on voter suppression in Georgia are valuable and seem all the more relevant given the new voter laws recently put in place.

Yes. Much of the issues Enjeti ponders upon will continue to educate, empower and be relevant. Be it the anti-Asian hate sentiment that killed Vincent Chin back in 1982 where justice has never been served or gun violence that continues to disseminate and renew fear as we learn that six of the eight victims shot in Atlanta massage parlors happened to be Asian American and the April 15 FedEx shootings where four of the victims happen to belong to the Sikh community. “All of our silences reproduce like spores, inhaled and exhaled into the ether, their growth exponential,” she writes, asserting all along that all emotions mean little unless translated into meaningful action.

Enjeti pens her most powerful prose in her unraveling of the ways in which heritage and identity shape activism, symbolically concluding with the fond restoration of her Avva’s (grandmother) cherished sari chest that reveals a jasmine flower upon completion of the artwork etched in it. The fragrance of white bloom sure spreads far and wide and lingers long, much like the insights imparted by the author. Fragrant. Far-reaching. Fulfilling.

ANJALI ENJETI is an award-winning essayist who writes about books, politics, and social justice. Her work has appeared in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Al Jazeera, Boston Globe, Washington Post, and other venues. Her debut novel, The Parted Earth, will be released in the spring of 2021. She teaches creative writing in the MFA program at Reinhardt University and lives with her family near Atlanta.