By Vikas Datta

Fittingly, I was in a bookshop when I heard about the death of Khushwant Singh. It was undoubtedly unexpected, for the grand old man had seemed on course to go on for ever. The news evoked a flood of memories – of standing in a bookshop and memorising jokes from his celebrated jokebooks (and the importance of knowing how to laugh at yourself), then relishing his accounts of travels to far-off lands, of his meeting all kinds of people (mostly VIPs) , his robustly outspoken views on various social and political issues and how interesting they seemed.

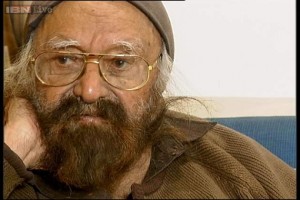

For this is the enduring importance of Khushwant Singh. He could be – and often was – quite opinionated, gossipy, (good-naturedly) malicious, sometimes bawdy and even raunchy, almost always provocative, an inveterate name-dropper but also self-deprecating, irresistibly witty and very, very readable.

And in the end, this is what counts. His longer works may not be counted among great literature, his shorter pieces may seem superficial and tending towards self-aggrandizement, but they will be read, remembered and evoke reactions – both positive and negative – something I suspected he always wanted.

A born raconteur, Khushwant Singh could shine across the literary spectrum, be it short essays – both travelogues and pen-portraits – short stories, novels and even plays with memorable settings and characters. I have not read all his published oeuvre but a considerable part of it though a long time ago and it has left a definite impression. An assessment of his work could easily fill a volume, so let me share some of I still remember.

Included in an anthology, possibly “The Vintage Sardar….”, I recall a certain play but forget its name – about a disparate band of tourists stranded in a forest guest house with a tiger on the prowl outside. The characters – the uptight bureaucrat, the naïve American travellers, the seemingly dissolute British hippy, the old slumbering guard – are well delineated while the mood moves from a mounting sense of unease towards an acceptance of the inevitable (and consequently living it up) before the unexpected denouement. Pity Khushwant Singh did not dabble in this genre more… he seemed to have a definite knack for it.

A perceptive and prickly observer of people, Khushwant Singh could also embellish the most humdrum of incidents and locales into something that would captivate you. It may seem dated now and is certainly overboard, but his account of Phoolan Devi, when she was on the run after the Behmai massacre, based on interactions with her family and a visit to her stamping area, is certainly worth reading.

Another incisive piece is an account of his visit to what is now Chhattisgarh when it was a part of Madhya Pradesh. It ends with a marvellous flourish – his paan-chewing guide, asked what a prolific-growing flowering (but useless) weed is called locally, turns his heads, spits out, and answers straightfaced: “Paalitishan (politician)”.

Khushwant Singh might not have been the first Indian to wander to exotic lands but he was definitely the first to write about the experience. Read of his visit to Papua New Guinea, where he encounters a Sikh working as the immigration officer, or his trips to Libya, Syria or Turkey.

He seemed to have loved to scandalise. Writing about Nargis, he recounts her request to let the family stay in his Himachal cottage (near Sanawar, where Sanjay Dutt was then studying) and agreeing to the request that he be free to tell everyone “she slept in his bed”. He also notes her burst of laughter and sporty acceptance.

Or the time, he runs into Shabana Azmi at a conference in Goa and manages to hug her when its time to part on the pretext it was Eid recently and, as he writes, he has go on to hug two Muslim journalists and a cleric too in the process.

It is easy to go on and on. But let me end with one of the jokes he sported in his column in the Hindustan Times. “A lady phones up a bookshop and says: ‘Please send me all the books you have by Khushwant Singh. Also send me something to read’.”

That could serve as a fitting epitaph – of the person, not the writer.