BY JYOTHSNA HEGDE

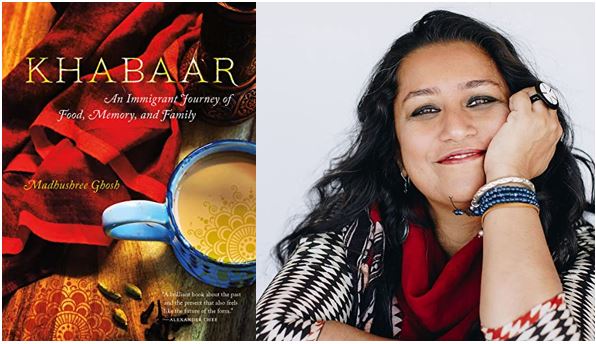

Khabaar (Food in Bengali): An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family

Author: Madhushree Ghosh

There is no sincere love than the love of food, George Bernard Shaw famously said. Khabaar (food in Bengali), Madhushree Ghosh’s memoir charts her unabashed and sincere love for food, amplifying the relationship between South Asian culture and its culinary traditions, elevating its significance from merely satisfying the palette to defining a higher purpose and calling.

Insightful and inspired, Khabaar unravels Ghosh’s own journey of self-discovery through food, delving deeper, braiding its connection to narrate journeys of colonization, migration, refugees, indenture, and domestic abuse. An ode to home cooks, chefs, and food stall owners alike, Khabaar includes recipes and pictures throughout, describing flavors and smells in intrinsic detail, uniformly arousing each of the reader’s senses.

Spanning over nearly two decades of her life, Khabaar chronicles Ghosh’s journey of love, loss, abuse, and survival, with immigrant stories blended with food that travels across the globe– from South Asia to Singapore to Durban to London to San Diego. Her nostalgia, about food in particular, is palpable, her sensibilities relatable to every immigrant who has felt homesickness, often questioning where home really is. Ghosh’s delectable writing invites readers to consider their own early food memories that transport us back in time, places and people we shared the moments with, even as she underscores the importance of how food helped her form her own identity and quenched her thirst for belonging in a foreign land as a daughter of refugees.

Ghosh’s competent craft shines throughout as she intertwines tales of prominent Indian chefs in America, their inspirations, struggles, and travails with her own. Ghosh winds up with the pandemic and its myriad consequences on her own life while preserving her parents’ memories through food.

In Peyaara Se Pyaar, with the focus is on guava (Peyaara), Ghosh writes about the family’s move to Delhi from Orissa (her birthplace) when she experienced being alienated and alone for the first time with a spoken language (Hindi) different than their own (Bengali), embarking on a journey of exploration of how they came to be immigrants and how she continues to seek the truth.

Tempted by a Guava, the only remaining of the last three, “To this day,” Ghosh writes, “I swear the peyaara (guava) said, ‘Eat me. Eat me now.” Her conversation with food had only just begun. While her dialogue with food continues to thrive to this day, Ghosh chose to channelize it to create socio-political awareness.

“We absorb the fish’s life. We live because they did,” were her Baba’s words of wisdom. “Never forget, Puchkey, fresh fish. For fresh life. Always.” Vivid and evocative, Ghosh invites us to her kitchen and fish market in Maacher Bazaar or Fish for Life, offering glimpses of her family who express love through teaching and feeding each other.

In Feeding the In-Laws, Ghosh observes her strained relationship with her ex-husband’s family while describing the rivalry between a pair of Indonesian prata restaurants.

In Search of Goat Curry, Ghosh highlights how she and her family searched for food in their new/adopted places, in this case, goat curry.

In When Indira Died, Ghosh recounts her favorite uncle and her Baba’s favorite brother, Shonajethu’s visit, the evening of the assassination of India’s then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, killed by her bodyguard, who was Sikh by religion. “He announces: See, now the violence will start. Just like the Partition.” She writes.

The Partition she refers to is the partition of 1947, when India was divided by the British before they left into Pakistan and India, divided by religion, Muslim and Hindu. There was genocide then. Ghosh writes about how her parents, children then, walked, rode trains, bullock carts into the Hindu-side of India. In 1984, they still talk about The Partition. “Refugees once, refugees forever.” “But,” young Ghosh tries to reason with her Shonajethu that is not the same. “This is between Sikhs and Hindus.” Her uncle replies: “Religion doesn’t matter once revenge is in the air.”

Search for Naroo is about the family’s trip to West Bengal, and how much these visits meant to them, when they returned “home” each summer, met with cousins and aunties spending lazy afternoons eating naroo and many a Bengali delicacy. Ghosh also skillfully toggles between the past and the present, narrating her harrowing experience of being trapped in her auntie’s haunted bathroom as a little girl and later in a hotel bathroom right before she is due for an important presentation. Being locked in a bathroom serves as a metaphor of her sense of feeling trapped in a vicious marriage with an abusive husband, who she was unable to confront for many years, until she finally did.

Orange, Green and White – With colors of the Indian flag as her backdrop, Ghosh writes about love that continues linger on despite abuse, separation and an official divorce. Much like the guava that asked to be eaten, an orange and green scarf on jaypore.com (both colors she despised), Ghosh writes asked to be bought- “Buy me. Wrap me around you. I am yours.” In a final declaration of her independence, Ghosh writes about wrapping the scarf around her neck, with her hair straight, loose, long, the way she never did before, because he didn’t like it loose, open, like that. “My skirt is a professional one, my jacket is dark. My scarf is bright and tells me I am not afraid anymore.”

Of Papers, Pekoe, Poetry and Protests in India is Ghosh’s emblematic protest of the CAA laws that led to mass protests all over India, when people came to the streets to voice their dissent against the government through poetry and protest. It is also her keen observations of the drawbacks of food culture, that includes social issues such as indentured servitude and racism or variations of classic dishes.

Celebrations await in Memory and What Makes a Family, are where Ghosh chooses to celebrate Diwali (traditionally Durga Pooja is considered a huge deal for people of Bengal), the festival of lights in her own way, highlighting poetry, friendship, food and love. Diwali is the symbolic celebration of good over evil – the end of a malevolent marriage she had held on for so long. It is also the celebration of light itself, the light she uncovered with her chosen family, establishing her own traditions as she shares the tikka masala, samosas, dal makhni, spinach paneer, cauliflower, and raita from Carlsbad’s Punjabi Tandoor, a favorite restaurant, and homemade naru, served with love and cherished with joy, laying foundations of a better and brighter future.

“The pandemic teaches us to look for joy when there is none, patience when it’s fleeting and hard to come by, peace when surrounded by fear,” Ghosh writes in her concluding essay, The Rituals of The Great Pause. “The Pause” paves way to a vegetable garden, a homage to her dad’s garden expanding the lens of food to life with a play of Bengali verbiage abaar which means again, aptly quoting “No wonder “again” remains part of “food” in Bengali, because khabaar means we bring it to our people abaar (again). And again. And again.”

Each of her essays serve as ingredients of her life’s dish, seasoned with the sensorial experience of visiting markets in Chittaranjan Park in New Delhi with her father, shopping produce, fish, and meat, to revel in the pleasure of gathering to eat homecooked Bengali food with pictures and recipes, flavored with closer examinations of racism, and injustice, layered with her own stories of immigration and surviving abuse alongside her family history extending from Partition through today, simmered to scintillating perfection, serving up an extraordinary culinary memoir. Grab a bite. The taste is unforgettable.

About the Author:

Madhushree Ghosh works in oncology diagnostics, and is a social justice activist. Her work has been awarded a Notable Mention in Best American Essays in Food Writing and a Pushcart Prize nomination. She lives in San Diego, California.