BY VEENA RAO

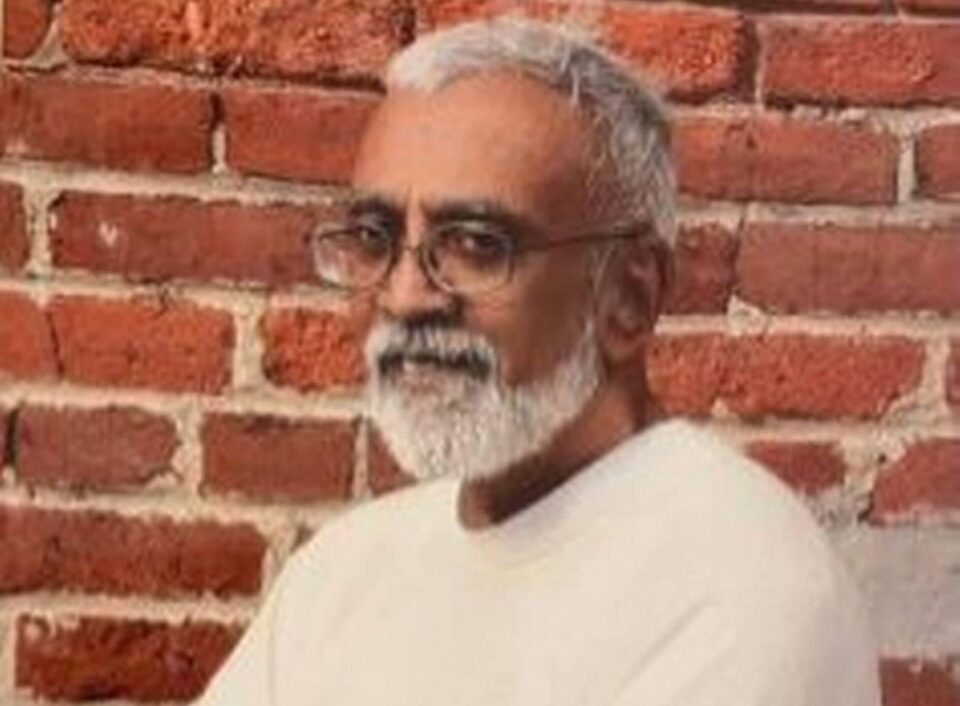

State College, PA, October 14, 2025: Subramanyam “Subu” Vedam walked out of Pennsylvania’s Huntingdon State Correctional Institution on October 3 a free man — or so he thought. After more than four decades behind bars for a murder he always maintained he did not commit, the 64-year-old Indian man expected to finally begin rebuilding a life stolen from him by a flawed justice system. Instead, moments after his release, federal immigration officers were waiting outside the prison gates.

Agents from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) immediately took Vedam into custody and transferred him to the Moshannon Valley Processing Center, citing a decades-old detainer issued in 1988. Three days later, ICE announced plans to deport him, despite his recent exoneration.

“After spending nearly his entire adult life behind bars for a crime he did not commit, Subu deserves a chance to live in peace, not face the trauma of deportation,” said one advocate with the Free Subu Coalition. “This is a grave injustice compounding another.”

The ordeal that upended Vedam’s life began in December 1980, when 19-year-old Thomas “Tom” Kinser disappeared in State College, Pennsylvania. His remains were discovered nine months later in a wooded sinkhole near Bear Meadows. Investigators zeroed in on Vedam, then a 19-year-old Indian student at Penn State, after learning Kinser had given him a ride on the day he vanished.

Prosecutors built a circumstantial case alleging Vedam had shot Kinser with a .25-caliber pistol during a dispute linked to a stolen synthetic ruby from a university lab. They claimed Vedam had test-fired a .25-caliber gun around the time of Kinser’s disappearance and used it to kill him. No eyewitnesses, fingerprints, or direct evidence tied him to the crime.

In 1983, Vedam was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole. He continued to assert his innocence, filing appeals that were denied. After a retrial in 1988, he was convicted again and returned to prison, where he would spend the next 42 years.

The case against Vedam was shaky from the start, but it wasn’t until decades later that its cracks became undeniable. Key evidence presented at trial — particularly the ballistic analysis — was later called into question. The prosecution insisted the fatal wound matched a .25-caliber bullet, but independent experts later concluded the bullet hole in Kinser’s skull was too small for that caliber, suggesting the weapon used was likely a .22.

Even more troubling, Vedam’s attorneys discovered that prosecutors had withheld crucial evidence from the defense. Among the undisclosed materials was an FBI forensic report detailing the measurements of the bullet hole — data that could have severely undermined the prosecution’s case.

“This was a textbook Brady violation,” said Gopal Balachandran, one of Vedam’s attorneys, referring to the landmark Supreme Court ruling that requires prosecutors to disclose exculpatory evidence. “Had the jury heard the suppressed evidence, there is a strong likelihood Subu would never have been convicted.”

In 2021, Vedam’s legal team filed a petition for post-conviction relief based on the newly uncovered evidence. After a series of hearings, forensic experts testified that the bullet hole’s size was inconsistent with the state’s theory and that the state’s ballistics evidence was scientifically unsound.

On August 28, 2025, Centre County Judge Jonathan Grine vacated Vedam’s conviction, ruling that the prosecution’s suppression of key evidence violated his constitutional rights. The District Attorney’s office subsequently dismissed all charges, citing the passage of time, the loss of key evidence, and the difficulty of retrying a 45-year-old case.

For Vedam, now 64 and Pennsylvania’s longest-serving exoneree, the judge’s decision should have marked a new beginning. Instead, it triggered a new legal battle. ICE agents, acting on a 1988 immigration detainer, arrested him as soon as he was released from state custody.

ICE has since confirmed its intention to deport Vedam to India. Because he was never a U.S. citizen — he came to the United States as a student and never naturalized — he remains vulnerable to removal, even though the criminal conviction that initially triggered the detainer has now been vacated.

Immigration advocates argue that using an outdated detainer based on a wrongful conviction is both legally questionable and morally indefensible. “The government imprisoned Subu for 42 years based on a miscarriage of justice,” said a spokesperson for the National Immigrant Justice Center. “To deport him now, after exoneration, is to perpetuate that injustice rather than correct it.”

Legal experts say the case could hinge on whether the vacated conviction can still be used as the basis for removal. Under immigration law, certain convictions trigger automatic deportation, but if a conviction is overturned, the legal grounds may no longer exist. ICE, however, could pursue other avenues, such as overstayed visa status, to attempt deportation.

As Vedam sits in an immigration detention center awaiting the next chapter of his legal battle, his supporters are calling for prosecutorial discretion, humanitarian relief, or even a private bill in Congress to allow him to remain in the country he has called home for more than 45 years.

“He was 19 when he was taken away,” said a family friend. “He has no ties to India, no family there. America is his home. Deporting him now would be another lifetime sentence.”

The case has drawn comparisons to other high-profile wrongful convictions, including those of Georgia’s Sonny Bharadia, who spent 22 years behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

For now, the man who lost his youth and middle age to a crime he didn’t commit faces the prospect of losing his home too. As one advocate put it: “Subu deserves a second chance, not a second punishment.”

Cover photo credit: bellisariostudentmedia.psu.edu/Vedam family.