BY VEENA RAO*

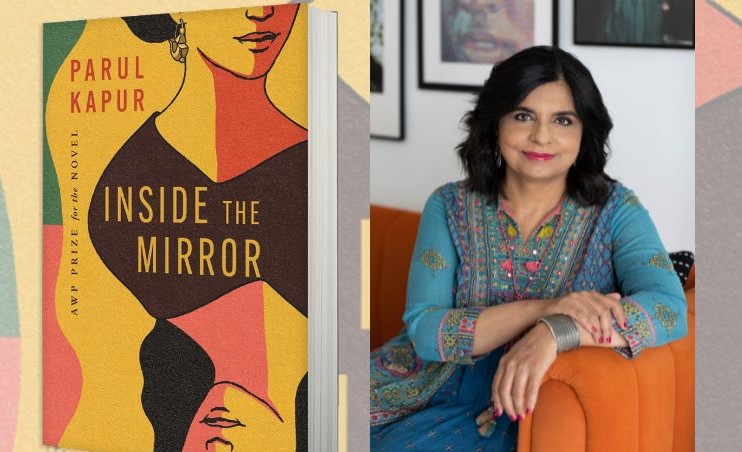

Inside the Mirror by Parul Kapur is a poignant exploration of women’s agency and ambition set against the backdrop of 1950s Bombay’s dynamic art scene. At the heart of the novel lies the struggle of twins, Jaya and Kamlesh, to carve out their identities within the confining societal norms of the time.

Kapur’s meticulous portrayal of a supposedly forward-thinking Punjabi family examines the pervasive influence of patriarchy, even in the progressive circles of the time. The twins’ father is a champion of education, but it is he who determines what the twin sisters will study. Jaya is to become a doctor, and Kamlesh a teacher. Their artistic expressions in art and dance are to remain merely hobbies.

“What is art? Is art a life?” the mother laments at one point. This question is central to the narrative and examines what happens when the characters choose art as life. Jaya and Kamlesh come alive as flesh and blood people with beating hearts that feel passion and pain in equal measures. Readers are immersed in the intricate dynamics and nuanced interactions between the sisters, their parents, and their formidable grandmother, Bebeji.

The novel also explores the power of art to preserve time and memory. Jaya finds solace in the knowledge that through her paintings, she can immortalize the people she has loved and lost.

Inside the Mirror is a deserving winner of the AWP Prize for the Novel.

Q&A with author Parul Kapur

In the Acknowledgements, you call the book your phoenix. Tell us about its journey.

I started writing Inside the Mirror in my early 20s, while I was in the MFA program at Columbia University. It was my companion for much of my life—through international moves, the birth of my son, and almost two decades of working as a freelance journalist. Part of the difficulty in finishing it was that I was writing about a time and place distant from me. If I’d gone to India for six months or a year, and steeped myself in the environment, I think I could have written it quickly. Instead, it took me twenty-five years to complete several revisions. And then I couldn’t find a literary agent, because the manuscript was too long at 600 pages.

In 2013, I interviewed the film director Deepa Mehta at the premier of Midnight’s Children, here in Atlanta, and asked if she would consider the manuscript for a movie. She agreed to read it. Ultimately, she declined to make a movie, but sent back an astute critique. On the basis of that, I drew up a detailed plan for a final revision. Yet I couldn’t bring myself to return to a book I’d already worked on for twenty-five years. So I gave up. Inside the Mirror sat in a box for ten years while I wrote another novel. A couple of years ago, I noticed some acquaintances were winning literary contests and getting their books published. My novel was too long for most contests, but the AWP Award Series didn’t have a page limit. I submitted Inside the Mirror and won. Then the University of Nebraska Press, my publisher, demanded I cut the manuscript significantly. So began an intense six months of editing and rewriting. I think it’s a much stronger book now that the story has been distilled. I’m delighted to see it making its way in the world.

What inspired you to write the story of Jaya and Kamlesh?

I was a young woman with a great ambition to be a writer when I began the novel. So I projected the dreams and doubts I had about becoming an artist onto my main characters, although they face far more opposition from family and society than I did. In college I’d become fascinated with visual art, and I’d dabbled in drawing and painting, so I gave Jaya the talent for painting that I wish I’d had. I’d also studied Bharata Natyam as an undergrad, with a disciple of the famous Balasaraswati, so I gave Kamlesh the natural talents of a dancer. Both dancing and painting are highly sensual arts, they can be exhilarating for the artist in the midst of their practice. Writing is cerebral and sedentary, so I enjoyed describing the sensuality and movement of painting and dancing.

Also, initially, the book was to be of a very different scale. I intended to write a multi-generational family saga that would play out over three decades post-partition. While it’s still framed by family drama, the story at heart is about these twin sisters in 1950s India, the era my parent came of age in. For a while, I managed to hide from myself that I wanted to write a novel about the dreams and ambitions of young women. Perhaps I’d felt it wasn’t an important enough story to tell.

The theme of women’s agency and ambition is central to your novel. How did you approach portraying Jaya and Kamlesh’s desires and struggles within the societal constraints of their time?

Jaya feels most alive and engaged when she’s painting, it’s how she connects with the world. Kamlesh lives an alternate life inside the mythology of Bharata Natyam. They are both dreamers to the extent that all artists are. Yet they are not rebels, they have great love for their family and don’t intend to betray them. It’s only when they become serious about their arts as their life vocations must they reckon with social prohibitions against a girl associating with a group of male artists or a girl displaying her body on the stage. That’s when their inner desires set them on a collision course with their parents and with society.

It takes research, lots of it, to accurately depict a bygone era. What were the sources of your research? And what were the challenges of recreating a Bombay of the 1950s, especially its art scene?

My primary source was people. I’m a journalist, so I’m used to investigating my subject through interviews. People from various walks of life who had experienced India in the 1950s spoke to me. I found the older generation had phenomenal memories. I’d also spent a year as a journalist in Bombay after college, so I came to know the city well, but I went back to research specific locations, such as Grant Medical College, where Jaya is a student, and Mehboob Studio in Bandra as a model for the studio where a movie is being shot in the book.

I came to know about the art world when I tracked down an important early modern painter, Mohan Samant, who was living in New York. I spent seven or eight hours at his apartment, listening to his recollections of the art scene in Bombay in the 1950s. The painter Nalini Malani also offered a vivid account of what it was like to be a woman artist in midcentury India, and the many ways in which women were sidelined by male artists.

The most challenging thing to grasp was the true atmosphere of the time. The 1950s were not simply the bright, hopeful times of my parents’ youth that I’d imagined, marked by the romance of the Hindi cinema and the glamor of big cities like Bombay. People’s lives, particularly the lives of the Punjabis, had been shattered by Partition. Some families continued to suffer tremendous hardship, including my father’s, who were refugees from Lahore. I had many conversations about the past with my father, but he never directly reckoned with the devastation his family experienced. He spoke of how they had coped, how his father scraped together an income, found a house in Delhi. Till today Indians have not come to grips with the trauma of Partition. It’s been swept under the rug, so they could try to rebuild their lives, which I understand. The twins’ in my novel are deeply affected by the sorrows of their relatives who had to flee Pakistan in 1947 and took shelter in their home. Their impulse to create art is a response to that pain.

Family dynamics play a big role in “Inside the Mirror.” How did you navigate depicting the complexities of familial relationships, especially between Jaya, Kamlesh, their parents, and Bebeji?

The personalities of the twins’ parents are very similar to my maternal grandparents, who were a progressive couple in the 1950s. Their father, though he’s a liberal man, holds most of the power. He makes the decisions over his daughters’ lives. They try their best to please him, and not set off his temper. But the women in the family aren’t without power. The girls’ grandmother, Bebeji, a former freedom fighter who served time in jail, is respected and obeyed. Their mother grew up in a wealthy family that cultivated the arts, so she encourages the girls’ arts as hobbies, in opposition to her husband. Between the twins, Jaya assumes a dominant role, emboldened by the fact that she’s a few minutes older. But the flip side of power is obligation and responsibility; whoever has power feels responsible for the welfare of the others.

The joint family, my father used to say, is a fortress for the weak and a prison for the strong. Though this isn’t a traditional joint family, the saying still holds true. The family is a prison full of love, which makes it hard to defy.

Love is another theme explored in your novel. How does the romantic relationship in “Inside the Mirror” intersect with the larger themes of identity, independence, and societal expectations?

Making decisions for herself, pursuing a man she is attracted to, choosing her vocation—these are all aspects of a woman’s self-creation. Of course, this was anathema in India in the 1950s. A woman was meant to be molded by her family and society. When Jaya becomes involved with a boy in medical college, it provides her some sense of agency over her own life. In my mind, it was important for her artistic and sexual liberation to occur simultaneously, each experience giving her a stronger sense of herself.

Jaya’s mother poses a profound question (which accurately sums up the tension in the novel): “What is art? Is art a life?” How do you interpret this inquiry within the context of Jaya’s journey as an artist, and how does it reflect broader themes explored in the novel?

Jaya has always gone after what she wanted, almost blind to social norms. This western notion of an individual artist, who is not part of a lineage or clan of artisans, was new to India. Certainly it wasn’t expected to be a woman’s vocation. Her mother’s words are meant to stress upon her the importance of family: a girl is supposed to be the caretaker of her family. She is the center of the household, without her that structure cannot exist. She holds it up. An artist’s strongest commitment is to their art—her mother has seen that in Jaya. So how can a girl be an artist? In her mother’s view, a woman cannot live a proper life without a family. But in Jaya’s view, she cannot live without making art.

Inside the Mirror is the winner of the AWP Prize for the Novel. How does it feel to receive recognition for your debut novel?

It’s thrilling after working on it for all these years and abandoning hope for a long time.

What do you hope readers will take away from “Inside the Mirror?”

I hope they will feel some sympathy for my characters who are trying to make their futures at a time when women’s lives were terribly restricted, and the society in general was so vulnerable, having been impoverished by the British and devastated by Partition. While that’s my hope, I’m interested in knowing what readers take away from it. A book is like a Rorschach blot. Everyone sees something different in it that relates to something in themselves.

Where can readers find you?

My website is: https://www.parulkapur.com and I’m on Instagram, @parulkapurwriter

*Veena Rao is an award-winning Indian-American author and journalist. She is the founding editor of NRI Pulse. Purple Lotus, her debut novel, is a 2021 American Fiction Award winner, a 2021 Georgia Author of the Year finalist, and an award-winning finalist in the multicultural and women’s fiction categories of the 2021 International Book Awards.