BY VEENA RAO*

“In these pages, my mother, my gangster, shall live. She was my shelter and my storm.”

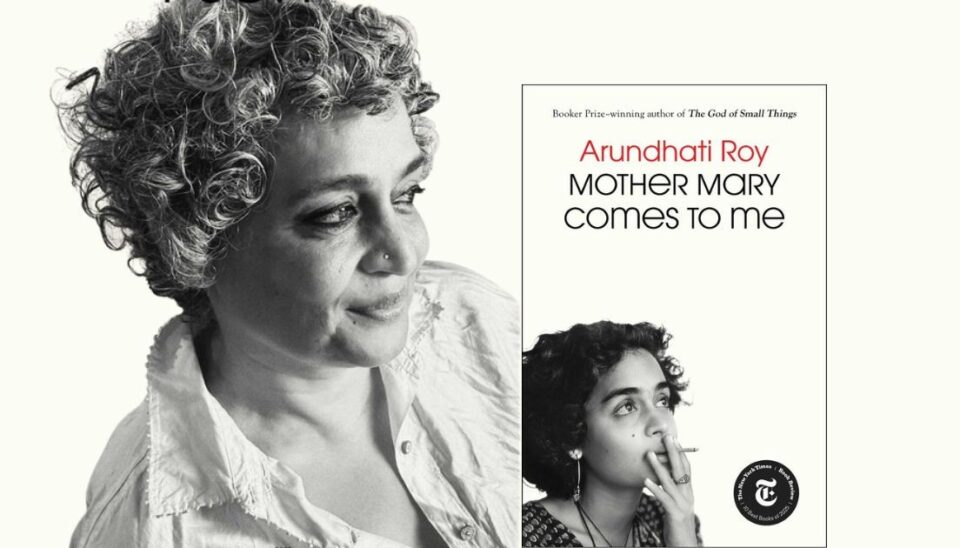

Arundhati Roy’s exquisite memoir Mother Mary Comes to Me is, at its core, an intimate exploration of her complicated relationship with her mother, the formidable Mary Roy—educator, women’s rights activist, and founder of the Pallikoodam school in Kerala.

Mary Roy is a force of nature, much like her daughter would become. In 1986, she won the landmark case Mary Roy v. State of Kerala, securing equal inheritance rights for Syrian Christian women in Kerala, India.

The author’s childhood is far from traditional. Raised by a single mother fiercely devoted to the school she is building, she and her brother LKC are expected to address her as “Mrs. Roy,” just like the other students. Though they are sent to prestigious boarding schools, their vacations are spent back in the school dormitories that double as their home, where they often find themselves at the receiving end of her mercurial temper.

Many of us who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s know a Mary Roy—the hot-tempered, iron-fisted, demanding parent. If not a parent, then a teacher, an uncle, or an authority figure who brooks no foolishness.

In one scene, a teenage Roy finds herself tongue-tied before a handsome young man. Her mother turns sharply: “You couldn’t think of a single intelligent thing to say? Do you think it’s nice for me to have people thinking that my daughter is a complete fool?” The scene ends with Mrs. Roy ordering the driver to stop the car by the side of the highway, asking her daughter to get out, and driving away.

Extreme? Yes. But the constant need for a child to look smart, talented, and impressive feels familiar. Many of us who grew up with strict, high-expectation parents recognize some version of it.

I was reminded of parents who show off their young children in front of guests, pushing them to sing, dance, play an instrument, or do whatever it is they are pushed to excel at. This expectation grows as the child grows. And if the child falls short? Disappointment. Rage. Guilt-tripping. Pressure.

Sometimes, the ones who love us the most are the ones who strike at our spirit until we grow small, bit by bit. In that sense, Mary Roy, the tyrannical parent, does not feel rare.

But this memoir is not simply a chronicle of a fraught mother-daughter relationship. It is also the story of Arundhati Roy’s becoming—fleeing home to Delhi (“I left my mother not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her”), her years at architecture school, her first love, JC, her marriage to filmmaker Pradip Krishen, her early foray into cinema, the years it takes her to write The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, and her years as an environmental and political activist.

It is also about her father, Rajib Roy, or Micky, as she calls him, whom she meets for the first time at age 23. Her mother refers to him dismissively as the “Nothing Man.” The contrast between her parents is striking. As Roy reflects, “His spirit is light and rascally. Hers so heavy, so unhappy.” And then comes the larger question she poses: “In the end, who is successful and who is not? Who can say? What is defeat and what is triumph?”

Roy uses the word “Lucky” as a standalone sentence several times in the book. I find myself lingering on that word, especially when reflecting on her publishing journey. She sends her manuscript for The God of Small Things to an acquaintance who has taken over HarperCollins India. He reads it, passes it to a writer friend, who forwards it to his literary agent, David Godwin. And that is that.

For the 99.99 percent of authors—published and unpublished—whose paths are paved with rejection letters from literary agents, this feels almost mythical. One might argue that her manuscript was Booker-worthy, and it is. But even Booker-worthy manuscripts can languish in slush piles. And I am sure it was especially so in the whitewashed publishing climate of the late 1990s.

To write a debut novel, sell it swiftly, earn enough to support one’s family for the rest of one’s life, and establish a foundation.

Uff! Lucky!

But to produce a novel so extraordinary that a major literary agent flies to India to meet you?

That’s not luck. That is literary genius!

Roy refuses to inhabit the trappings of upper-class life. When Pradip inherits his parents’ large home in an elite Delhi neighborhood, she chooses instead to move into a modest two-bedroom apartment.

Her activism—her involvement with the Narmada Bachao Andolan, her time embedded in Naxal-affected villages—is an essential part of the memoir. For readers unfamiliar with that aspect of her life, these sections provide necessary context. Take it or leave it, this is who Roy is.

As I read, the journalist in me keeps surfacing. I find myself researching not only the principal characters but also the setting. What does Pallikoodam, that Laurie Baker–designed school nestled in Kerala, look like? How does Ayemenem appear today, and what does the Meenachil River look like in the light Roy describes? What does Mary Roy sound like in her interviews? What about her brother, G. Isaac? Who is the real-life “JC,” the first boyfriend? I even revisited In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, which I remember watching years ago on Doordarshan—its screenplay written by Roy herself, who also acts in it, directed by her then husband, Pradip Krishen. And, of course, the big question: How would Mary Roy react to her portrayal in her daughter’s memoir?

Mother Mary Comes to Me moves at a brisk pace and reads like a page-turner. Roy has lived an extraordinary life, and she tells it in the lyrical, fearless style she is known for. The structure is tight, the scenes vivid, and the voice unmistakably Arundhati Roy.

In the end, this is a book many daughters (and sons) recognize. Because they, too, are raised by men and women who are strong, flawed, demanding, loving. Roy’s memoir reminds us that our parents shape us in ways we spend a lifetime understanding. And sometimes, writing is the only way to make sense of it.

Cover photo credit: Simon & Schuster.

*Veena Rao is the founding editor of NRI Pulse and the author of the novel, Purple Lotus.