BY VEENA RAO*

“If you don’t have love, you don’t properly exist. If you don’t properly exist, you don’t have love.”

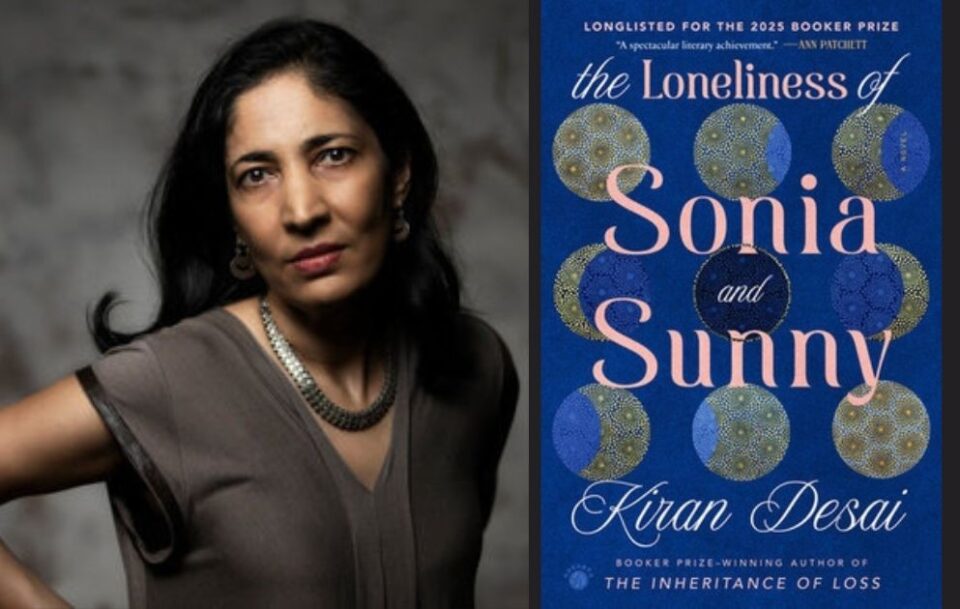

Kiran Desai’s Booker short-listed new novel, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, is a sprawling, 673-page meditation on loneliness, displacement, identity, and love—not love in the traditional romantic sense, but love in all its unsettling and contradictory forms. Desai examines love that abuses and love that accepts abuse; love that never quite materializes and love that abruptly ends; a mother’s love that smothers, and a son’s love that longs for escape.

The book is set in the mid-1990s to early 2000s, when people still used landlines to communicate, and obtaining a green card did not take forever. Sonia, an aspiring novelist battling loneliness, is studying at a university in Vermont when she enters into a relationship with Ilan de Toorjen Foss, an artist thirty-two years her senior. The relationship is controlling and emotionally abusive, and it ends predictably, leaving Sonia shattered and driving her back to India. Sunny, a Columbia graduate, works night shifts at the Associated Press in New York. He has an American girlfriend and has moved to the United States partly to escape the suffocating influence of his mother, though her presence continues to shadow his adult life. Though Sonia and Sunny have never met, their families once attempted to arrange a marriage between them. Later, when Sunny travels to India to visit his grandparents, the two meet by chance on an overnight train—an accidental encounter that forms much of the story.

The plot is interesting (dramatic even), but too many digressions and stretches of description and inner monologue slow the story down. While reading this novel, I was reminded of feedback I once received from my developmental editor on an early manuscript of my own. Somewhere hidden in this marble is a beautiful sculpture, she said. The challenge is to chisel away the excess to find the masterpiece. That observation returned to me repeatedly as I read The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, a book nearly twenty years in the making.

The novel begins with promise. I was immediately drawn into Sonia’s life in cold Vermont, her grandparents’ rigid world in Allahabad, and Sunny’s existence in New York under the lingering shadow of his mother in Delhi. It is in the middle—arguably the most difficult part for any writer—that the narrative begins to meander. More than once, I found myself skimming pages and asking whether what I was reading was essential to the story of Sonia and Sunny.

At almost 700 pages, the novel demands a great deal from its reader. Such a commitment naturally raises expectations of emotional and narrative payoff. That reward, however, feels uneven. Often, it seems like the novel tries to take on too much. Extended passages devoted to minor characters who appear only once or twice interrupt the narrative flow. The book tackles an abundance of themes—class, migration, loneliness, gender violence, power, identity—and strains under their collective weight. Certain plot elements, such as Sonia’s sexual assault, feel extraneous, raising the question of whether they are necessary to the novel’s emotional core.

As a result, despite initially rooting for Sonia and Sunny, there came a point when my emotional investment waned. Both characters’ growth feels stalled due to the weight of extraneous words. Amid the world-building and character-building, the central character arcs sometimes seem forgotten.

The novel spans multiple countries, moving from Vermont and New York City in the United States to Delhi, Allahabad and Goa in India, to Italy and Mexico. The constantly shifting locations give the book the feel of a travelogue at times, with many pages spent observing place instead of advancing the story.

That said, the novel has many strengths. The principal characters—Sonia, Sunny, Babita, and Papa—are layered and textured, and even minor figures such as Sunny’s friend Sathya and Sonia’s aunt Mina Foi are vividly drawn. Desai’s prose is beautiful and offers deep insights into the human condition.

Immigrants will recognize the particular loneliness Desai evokes—not of isolation alone, but of living between cultures, and homes where one never fully belongs. I began reading the book while vacationing in India and finished it a day after returning to Atlanta, which made Desai’s world of displaced, lonely characters feel especially personal.

“One thing seemed certain: If India existed, then America could not, for they were too drastically different not to cancel each other out. Yet despite this fact, they refused to remain apart. India invaded his life all the way from the other side of the world, and then life here became instantly artificial, a taunt. He became an impostor, a spy, a liar, and a ghost.”

How often have we felt that way?

The novel’s elements of magical realism did not work for me overall, though the storyline involving the loss and recovery of the Badal Baba amulet stands out. It is through Badal Baba that the author lays out the novel’s final message, which I shall refrain from talking about here, to avoid giving too much away.

The novel lingers, despite the flaws. I found myself thinking about its characters and their interior lives long after finishing the book, even as I recovered from jet lag.

*Veena Rao is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of NRI Pulse and the author of Purple Lotus, a novel.