BY MONI BASU*

On a warm April day in 1978, my father and I drove 160 miles east from our house in Tallahassee to Jacksonville. It wasn’t to frolic on a beach or to go shopping at Regency Square mall. There was nothing like that in Tallahassee and we marveled at its marble floors and water fountains. No, this was a far more important mission. It was to be a day that would determine the rest of my life in America.

A letter had arrived a few months earlier telling Baba that his daughter was to appear for an interview at the regional Immigration and Naturalization Service office. We were summoned to appear at 10 a.m. at University Hospital on 8th Street for a medical examination that would cost $20, and then immediately head to Room 227 of the Post Office Building on Monroe Street.

Even though Jacksonville was an easy drive, a straight shot down Interstate 10, my father did not want to be late. I wore the best outfit I had, a rust-colored dress purchased at Casual Corner. What if we couldn’t find the right office? What if we missed our place in line and had to start the process all over again? My father considered this to be a singularly important event and rushed me out of the house just after sunrise.

The typed instructions were clear: We were to carry the sealed envelope bearing the results of my medical tests, my passport, two photographs and my 1-94, the document issued upon entry to the United States that contains the date of entry, how long a person is allowed to stay and what kind of visa was issued. In our case, it was an H-1 visa, reserved for people like my father who possessed distinctive skills, people who were considered high value professionals.

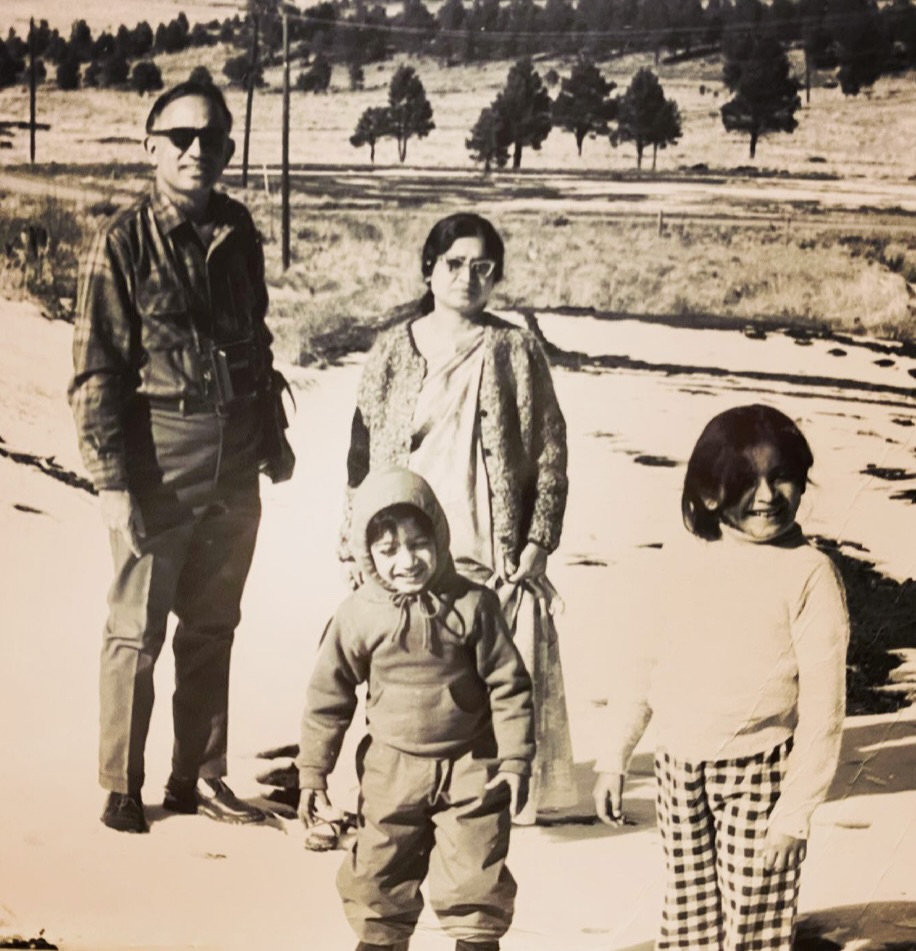

Baba was a renowned scholar in his field of probability theory, and in 1975, Florida State University had offered him an attractive teaching position. But the H-1 visa was temporary. We were now seeking permanent residency, which perhaps would one day lead to citizenship.

After a lifetime of moving from one university to the next, my father had chosen to finally settle down in Tallahassee. The FSU Department of Statistics, one of the first standalone departments in the United States, had earned a strong academic reputation, especially in Bayesian statistics, which was my father’s love. FSU stood head-to-head with Berkeley, Stanford, Harvard and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Another reason was that Baba was losing his eyesight to macular degeneration and he wanted to live in a smaller town where life, he thought, would be easier. I suspect Baba had grown tired of accepting visiting appointments around the world that kept us constantly on the move. He yearned to own a house, grow a garden, play chess every night and walk to the office each morning, eager to brainstorm with his Ph.D. students.

I don’t recall many of the details of my interview that day before the INS agent. Only that the room was a color similar to the mint green walls common in prisons. And that the agent was a white man who didn’t look like he would be fun to hang out with. He had a file with my A number. A for alien. I don’t remember what questions he asked me except that towards the end of the interview, he looked at me with great consternation. I had no birth certificate. No adoption certificate. My parents had no marriage certificate. These kinds of documents were not common when I was born in 1960s India.

“As far as I’m concerned,” the man said, “you don’t exist.”

His words hung in the air like suffocating smoke. I couldn’t tell if I was still breathing or if I had been erased altogether.

It was the last thing I needed to hear. I was 15 and a hot mess. I suppose you could say that about any teenager but I was a teenager in a new school, new city, new country. I wanted to do all the things the “cool girls” did. Drinking. Smoking pot. Staying out late. Kissing boys in the backs of cars. All the things that would help me fit in. All the things my father did not approve of. The things he could not understand.

Baba was a brilliant man who had hailed from a culturally conservative society. Up until high school, I had been daddy’s little girl. My father and I rarely sparred. But all that changed in 9th grade when I began attending Amos P. Godby High School in Tallahassee. And just like that, Baba became my enemy. Years later, he would write me a letter acknowledging the prickliness of those years. He knew I had filled up journal after journal with my teenage angst. I wonder now if he had secretly read them.

On that day in the INS office, no words left my mouth. Everything after “you don’t exist” blurred in my mind. That agent erased me; I erased the memory of him erasing me.

It took a lot of finagling for me to convince the United States Department of Justice, the federal entity that then oversaw matters of immigration, that I was worthy of becoming a permanent resident of this country. The only document Baba could produce was an affidavit sent by my mother’s brother, a court magistrate in India, stating that my parents had adopted me seven days after my birth.

I knew Baba had been nervous. He did not want to return to Kolkata because we could not secure a permanent visa to remain in America. We were lucky. A few months after that trip to Jacksonville, my parents and I received our green cards, which did indeed have a green cast to them back then. My mother became a U.S. citizen in 1984. My father retired prematurely from FSU in 1986, after a massive stroke left my mother in a wheelchair and my parents decided life would be easier for them in Kolkata. I was naturalized in 2008 and cast my first ballot ever in the presidential election that year. I have lived in this country now for 50 years.

In 1990, the H-1 visa was reinvented as the H-1B, and it boomed alongside the rise of Silicon Valley. Most H-1Bs are awarded to technology workers, though other fields also benefit. And these days, almost 70% of the visas are awarded to Indian nationals.

But now, Donald Trump has taken aim at the H-1B guest worker program. In September, the Trump administration began imposing a $100,000 fee on new H-1B petitions. This, of course, is sure to impact an employer’s ability to bring the world’s most skilled workers to this country. On Wednesday, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a supporter of all things MAGA, ordered education officials to “pull the plug” on H-1B visas for foreign workers at state universities — the kind of worker my father was in 1975 when FSU hired him. DeSantis said such jobs should go to Americans.

I fear Florida’s universities will suffer from not being able to attract the very best of academia from all over the world, like my father, who was a trailblazer in the world of Bayesian statistics and produced the Basu Theorem. I fear limiting H-1B visas may greatly slow innovation not just in academia but in every sphere. Think of all the computer whizzes, engineers, doctors, nurses, financial analysts and yes, mathematicians and statisticians, who may never step foot in this country because of Trump’s fees. They are not people who displace Americans in the workforce. To the contrary, they add to our collective brain.

I am a direct beneficiary of the guest worker program. I would not have the life I do now had I not come with my father on his H-1 visa and subsequently attained a green card and citizenship. What if in 1975, Florida State had spurned Baba not on merit but because there was no visa that would allow him to enter the United States to teach?

When I filed a freedom of information request to obtain my immigration records, I had hoped they would include the name of the INS agent who interviewed me on that April day in 1978. They did not. I so wanted to thank him for allowing my case to move forward, even though it was lacking in the documentation department. And I wanted to tell him one more thing. That I do, indeed, exist.

*Moni Basu is an award-winning journalist, author, and director of the low-residency MFA in Narrative Nonfiction and the Charlayne Hunter-Gault Writer in Residence at the University of Georgia. She previously served as a senior writer at CNN and a reporter at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among other publications. Her previously published pieces on the H-1B visa topic include Why the highly coveted visa that changed my life is now reviled in America and Nationality, identity and the pledge of allegiance.