BY JYOTHSNA HEGDE

When you sit across from B. Suresha, you quickly realize that his presence is not dominated by loud declarations or flamboyant anecdotes. Instead, there’s a quiet depth about him — an air of someone who has observed life closely, lived it richly, and translated those observations into stories that matter. He is truly grounded and profoundly thoughtful, qualities that run like an invisible thread through his long and varied career in cinema, theatre, and television. It was with this same reflective clarity that, during his Atlanta visit, he spoke at length with NRI Pulse about his views on storytelling and the arts.

“Be political.” With these two words, B. Suresha sets the stage—not just for his life’s philosophy, but for the art he creates, the struggles he endures, and the cultural space he inhabits. For him, politics is not simply about governments and parties; it is about choices, survival, responsibility, and the courage to tell stories that matter. “Don’t say you are apolitical,” he insists. “Every time you choose something—even a bar of soap on a supermarket shelf—you are making a political choice. Be a political human being. Choose rightly, choose wisely, and enjoy this moment.”

That clarity of thought has defined his journey — from a child actor in one of Kannada cinema’s greatest films to a director, writer, producer, and actor whose work continues to challenge, inspire, and reflect society.

That idea—that life itself is political—has defined the arc of Suresha’s journey. Born into modest circumstances, his early years were shaped by questions of survival. “Every time the issue of survival came,” he reflects, “I had to find methods, I had to find a path. Not just for me, but for my family, my mother, my brother, who was fighting his place as a friend. That made me fight back.” That fight—quiet, stubborn, poetic—has carried him through decades in the Kannada cultural world, first as a writer and then as a filmmaker.

Early Life in Davangere and Bengaluru

Born in Davangere, Suresha moved with his parents to Bengaluru at the age of seven. His parents, both employees of ITI, raised him in Hanumanthanagar, where he was drawn to the arts early.

He recalls fondly: “As a child, I would go to A. S. Murthy’s Kalamandira to learn painting and theatre. It was like a second home.”

His education was as unconventional as his artistic choices would later be. He studied at Women’s Peace League, a cooperative school, before moving to Bangalore High School. Later, he earned a diploma in ceramic technology from S J Polytechnic, a Bachelor of Engineering (BE) from Jadavpur University, and an MA in Kannada from Mysore Open University.

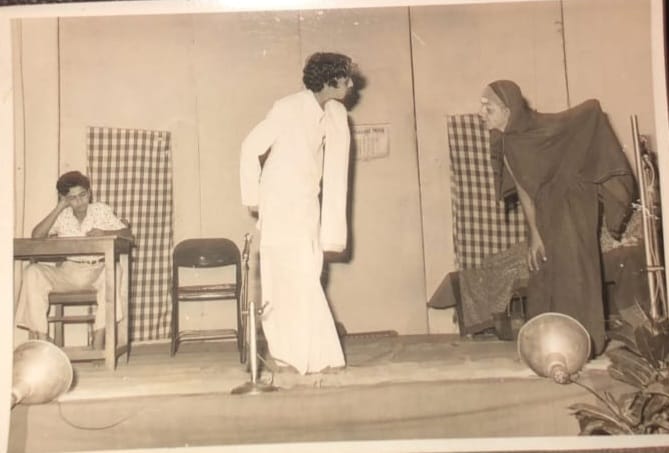

In 1981, he joined BHEL as a supervisor, where he balanced a demanding day job with his passion for theatre at night. “I would work at the factory during the day and then spend evenings writing plays or rehearsing,” he remembers. “Theatre kept me alive.”

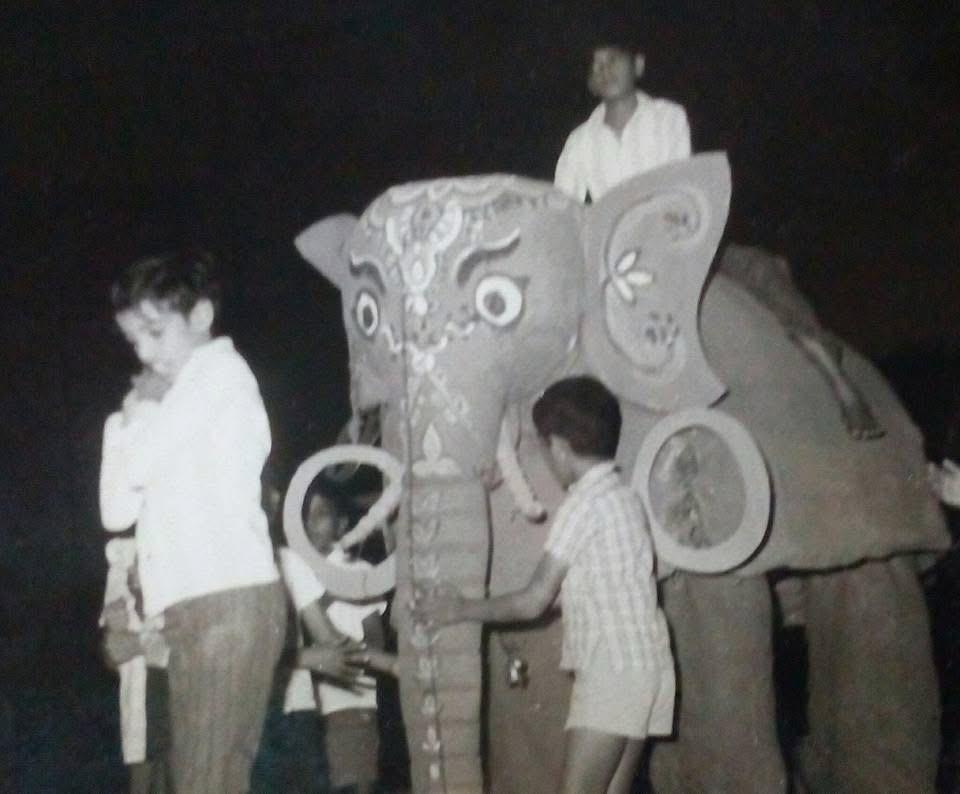

Beginnings in Cinema

Suresha’s tryst with cinema began at just eleven years old when he appeared in Girish Kasaravalli’s Ghatashraddha (1977). The film went on to win the National Award for Best Feature Film and is still hailed as a landmark of parallel cinema.

“When I acted in Ghatashraddha, I never imagined cinema would become my lifelong language,” he reflects. “But that experience planted a seed I could not ignore.”

It was on the set of Kasaravalli’s directorial debut, Ghatashraddha, that Suresha first tasted the essence of cinema. There, amidst the quiet discipline of parallel cinema, the seeds of his own creative philosophy were sown. He learned not in the sterile halls of academia, but in the living, breathing crucible of a film set, where every frame was a lesson and every scene a masterclass in social consciousness. This initial encounter imbued his work with a deep-seated respect for social issues and the power of storytelling.

Kasaravalli, he explained, instilled in him a sense of discipline and the art of structuring narratives with intention. “It wasn’t just the three-act formula that Syd Field talked about,” he reflects. “It was about finding an Indian narrative structure — a way of carrying the audience along and leaving them with something meaningful to reflect upon.” What impressed him most was Kasaravalli’s meticulousness: the careful nuances in his scripts, the thought behind every frame, and the way he used cinema to drive home a point without ever being didactic. For the young storyteller, this was a masterclass that shaped not only his craft but also his vision of cinema as a medium rooted in culture and responsibility.

Suresha recalls those days with his trademark humor and humility. He laughs when he remembers how he once misheard the term OSS shot (Over-the-Shoulder shot) as “Oasis.” “For the longest time, I thought people were referring to something mysterious called Oasis,” he jokes, “and I didn’t dare to ask what it was!” Such small confusions never deterred him — instead, they became part of his learning curve. “Every great filmmaker starts by fumbling,” he says, “and I was no different.”

Like a stream that finds its way from a mountain spring, Suresha’s career flowed into more commercial valleys, yet it carried with it the pure, clear water of Kasaravalli’s influence. His films, such as the critically acclaimed Puttakkana Highway, bear the indelible mark of that early tutelage—a commitment to adapting profound literary works and a compassionate gaze upon the struggles of ordinary people. Though their styles diverge—Kasaravalli’s a whisper of neo-realism, Suresha’s a more resonant voice—the echoes of their shared heritage are undeniable. Suresha’s focus on compelling narratives and richly drawn characters is a tribute to the very soul of parallel cinema, a testament to the master’s hand that first guided his own.

Soon after, he began assisting both Kasaravalli and S. Ramachandra, learning everything from scriptwriting and editing to simply holding the clapboard. These small but vital experiences shaped his understanding of cinema as craft, not glamour.

Suresha’s life in theater and cinema took a significant turn when Shankar Nag moved to Bengaluru in 1982 and established the group Sanket. At just 22, Suresha was assisting his mother at her printing press when he met Nag. Their conversations about cinema and theatre left a lasting impression, and Nag, noticing Suresha’s beautiful handwriting, hired him to copy scripts. This apprenticeship soon grew into something much larger —Suresha was part of Nag’s team on projects such as Accident (1985), a searing political thriller, and the timeless television series Malgudi Days (1986), based on R. K. Narayan’s stories.

His foray into the Literary world

From a very young age, Suresha discovered that stories were his natural medium of expression. He recalls with a smile that when he was in the sixth standard, he penned his very first short story — a tale about a devout family torn apart by the tensions between tradition and modernity. To his surprise, it was accepted by a small country magazine, and he received a princely sum of five rupees as payment. “That was my first remuneration,” he says. “I was so happy with it.” That early validation set him firmly on the path of storytelling.

His First Short Film

In 1984, fortune and conviction intersected. When Suresha received a 20% bonus from his factory job — about ₹16,000 — he decided to finance his first short film. He handed the script to Shankar Nag, who read it, suggested changes, and offered to produce it under the Sanket banner with a check for ₹8,000.

The short film, Haggada Kone, earned recognition at film festivals and gave Suresha the courage to leave BHEL and pursue cinema full-time.

From Script to Screen

The 1990s saw Suresha transition into writing. He collaborated with popular actor-director Ravichandran in 1993, showcasing his flair for crafting dialogues that resonated with both emotion and wit. Around the same time, he found success in television, directing serials such as Hosa Hejje (1991), Sadhane (on Doordarshan), and Naaku Thanthi. These serials became household names in Karnataka, establishing him as a versatile creative force who could move between cinema and television with ease.

As he often explains, his ability to direct and act in television serials, and later to produce big-budget, mass-appeal films with popular stars, allowed him to sustain the more socially conscious, politically rooted films that rarely generated significant revenue. “My political and social reality cinemas don’t bring much money,” he acknowledges candidly. “So I fund them by working in television and producing commercial films that have mass appeal. That balance keeps me going.”

By the early 2000s, Suresha was ready to take the director’s chair. His debut directorial, Tapori (2002), was followed by Artha (2003), a film that not only earned him the Karnataka State Award for Best Director but also established him as a filmmaker who could balance human drama with cinematic craft.

But it was Puttakkana Highway (2011) that became his signature film. Adapted from a short story by Nagathihalli Chandrashekhar, the film told the story of displacement and development through the eyes of rural characters. It won the National Award for Best Feature Film in Kannada, cementing Suresha’s reputation as a storyteller unafraid to engage with social realities. Films like Devara Naadalli (2016) and Uppina Kagada (2017) further cemented his reputation as a filmmaker who combines realism with conscience.

An Actor of Substance

Just when audiences had come to think of him as a filmmaker, Suresha reintroduced himself as an actor. Beginning with Slum Bala (2008), he went on to appear in films like Ulidavaru Kandanthe (2014), Jatta (2013), and Benkipatna (2015). His roles in the blockbuster K.G.F: Chapter 1 (2018) and its sequel made him recognizable to a new generation of viewers.

Acting, for Suresha, isn’t just a side pursuit. It is another form of storytelling, a way to inhabit perspectives different from his own. His performances are marked by subtlety and restraint, much like his personality. They remind us that sometimes the quietest characters leave the loudest impressions.

But acting, he says, is not about visibility. “When I act, I try not to be seen. I want to disappear into the character. That is the only way the story comes alive.”

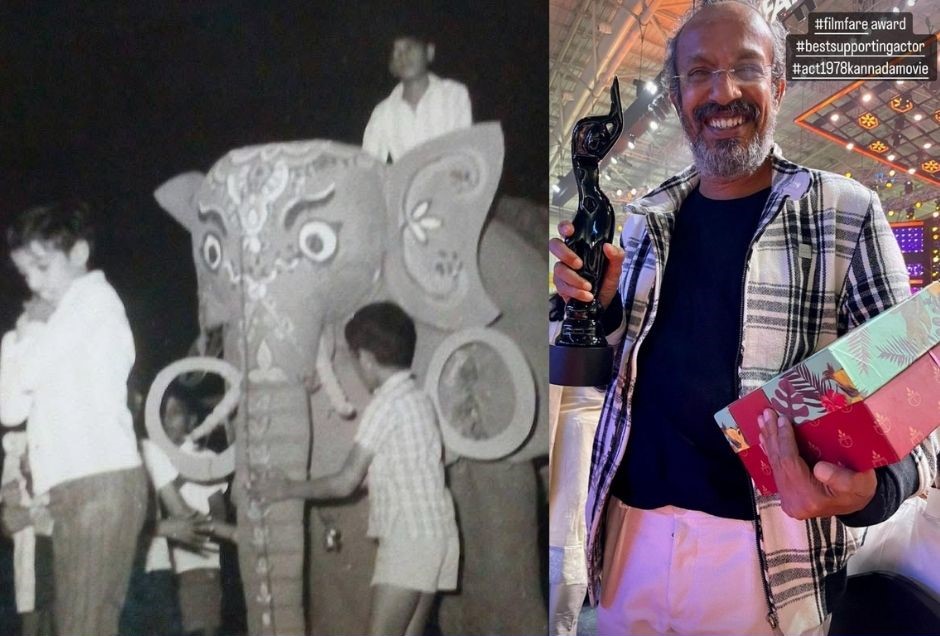

His performance in ACT 1978 (2020) earned him critical acclaim and an acting award, proving that his versatility extends across mediums.

Theatre, Family, and Media House

Theatre remains his grounding force. “In theatre, there are no retakes. The audience tells you instantly whether you are honest. That honesty is what I carry into my films.”

The stage also brought him his life partner, Shylaja Nag, when they worked together on a Macbeth production in 1988. They married in 1992 and co-founded Media House, a production company behind films like Naanu Nanna Kanasu (2010), Sakkare (2013), and Yajamana (2019).

“Shylaja is my strongest critic and my biggest collaborator,” he says. “Together, we take creative risks we may not dare to take alone.”

Their daughter, Chandana S. Nag, is now continues the family’s creative legacy.

The Legacy of Vijayamma

Suresha often credits his mother, Vijayamma, for nurturing his love of books and ideas.

To understand B. Suresha’s worldview, one must also look at the towering influence of his mother, Vijayamma. She was more than a parent; she was a pioneer. Recognized as the first woman journalist in Kannada, Vijayamma broke barriers in a field dominated by men. Fondly known as the “Devi of Kannada,” she played a key role in bringing the International Film Festival to Bangalore, thereby opening up Kannada audiences to global cinema.

Her contributions extended far beyond journalism. She launched Ila Printers, a publishing house that gave space to women writers, and initiated Namma Manasa, a women-focused intellectual magazine. At a time when women’s voices were often marginalized, Vijayamma created platforms to amplify them.

This spirit of courage and social commitment clearly influenced Suresha. His films often explore the struggles of ordinary people, the marginalized, and the voiceless — a reflection of the values his mother embodied. Creativity, for him, is not just art; it is responsibility.

Suresha speaks of her with deep admiration: “My mother taught me that the written word and the moving image both carry power. She believed every voice deserves to be heard, especially women’s voices. That belief lives in me, too.”

Beyond the Camera

Suresha has never limited himself to just one role. Whether it is writing dialogues for classics like Mithileya Seetheyaru (1988) and Harakeya Kuri (1992), acting in diverse roles across genres, or producing films that balance art and commerce, he has remained a creative chameleon. He has also authored books and remained connected to the world of theatre, ensuring that his artistic roots stay nourished.

“Theatre keeps me honest,” he says. “When you stand in front of a live audience, there is no editing, no retake. It reminds you why you became an artist in the first place.”

Recognition and Awards

His work has earned him numerous accolades, including the Karnataka Sahitya Academy Award (1996) for his play Shaapurada Seeningi Satya, multiple Karnataka State Film Awards for Artha, and a National Award for Puttakkana Highway. More recently, his role in ACT 1978 (2020) brought him awards for Best Supporting Actor at both the SIIMA Awards and the Filmfare Awards South.

These recognitions are not just trophies on a shelf; they reflect a career that has consistently strived to merge artistic excellence with social relevance.

OTT Platforms

On OTT platforms, Suresha is pragmatic. He pointed out that only a small percentage of films actually make it to the streaming space. “Out of hundreds of films made, barely five to ten percent get picked up by OTT platforms,” he observed. While digital platforms have created new opportunities, he is clear-eyed about their limitations. “For most filmmakers, OTT is not a guarantee. It’s a bonus if your film is chosen, but cinema cannot depend on it entirely,” he explained.

Instead, he believes theatre and television continue to play equally vital roles. He often recalls his own years working on serials like Hosa Hejje and Naaku Thanthi, which connected with audiences across Karnataka. “Television taught me discipline and consistency — you had to write, shoot, and deliver every week, and that rhythm built a relationship with audiences that OTT can’t replicate,” he said. For him, the stage still remains the most intimate medium of all. “In theatre, there is no camera to hide behind. The audience breathes with you, and that truth is irreplaceable,” he reflected.

A Voice Rooted in Kannada Soil

To understand B. Suresha is to understand Kannada cinema itself. The Kannada film industry—often overshadowed by the larger industries of Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu—has historically been a crucible for bold, socially conscious storytelling. From Puttanna Kanagal’s psychological dramas to Girish Kasaravalli’s meditative films that carried Kannada cinema onto the global stage, the industry has long nurtured auteurs who take risks. Suresha stands firmly in that tradition. His work bridges popular appeal and social commitment, the personal and the political.

The Kannada screen has always been different in texture: deeply local, rooted in the soil of Karnataka, yet open to global winds of change. In the 1970s and 1980s, filmmakers experimented with neo-realism and regional modernism. In the 1990s and 2000s, when television and later the OTT revolution began altering viewership patterns, Suresha was among those who adapted, innovated, and found ways to reach audiences without losing integrity.

What He’s Working on Now

Even today, Suresha’s creative well shows no signs of running dry. He is currently directing a play based on a folk story called Uguru Deepa—a powerful narrative about three generations of women, where a traditional lamp becomes the storyteller of a young woman accused of an extramarital affair, and how that very lamp helps her find freedom and dignity. The play, written by a respected Kannada author, is being staged with Nataranga, a legendary theatre troupe in Karnataka that is reviving itself after more than 1,500 years of tradition.

Alongside this, Suresha is evaluating six screenplays submitted to his production company, balancing his role as a director, mentor, and producer. His days are carefully structured—he dedicates at least two to three hours daily to reading, always searching for the next great story to bring to life.

His Message to the World

When asked what advice he would give to aspiring artists, whether in theatre or cinema, Suresha offers the same reflective clarity that has guided his own journey: “Enjoy this moment. If you forget to enjoy today, and if you lose yourself in yesterday or tomorrow, you are wasting life. Construct with what you have for a happy today, not for tomorrow. Be in this moment.”

And then, with the same conviction that has shaped his art, he reiterates: “Be political. Don’t say you are apolitical. Every time you make a choice—even something as simple as buying soap—it is political. You cannot escape it. So be a political human being. Choose rightly, choose wisely, and enjoy this moment.”

The Man Behind the Stories

What makes B. Suresha remarkable is not just the list of films, awards, or roles, but the way he approaches life. He listens intently, speaks with purpose, and creates with conviction. His humility makes him approachable, while his thoughtfulness makes him unforgettable.

As he reflects on his long journey, he says simply: “I don’t measure my career by success or failure. I measure it by whether I stayed true to the story.”

In a cinematic world often obsessed with spectacle, B. Suresha stands as a reminder that art is political, responsibility is creative, and stories rooted in conscience endure far longer than trends. B. Suresha is not just telling stories — he is shaping cultural memory, one frame, one performance, one play at a time.