BY VEENA RAO

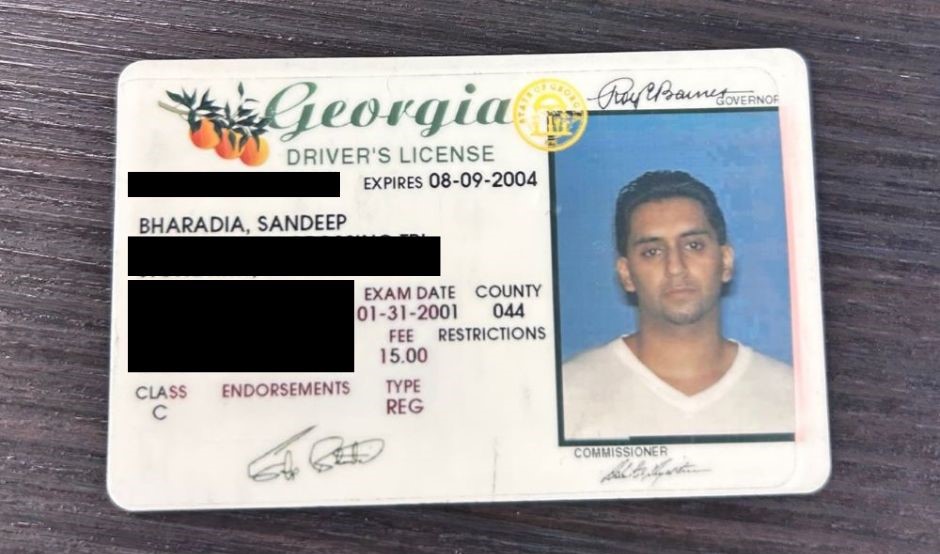

Atlanta, GA, September 15, 2025: It began like any other day in late November 2001. Sonny Bharadia was 27, working steady hours in sheet metal, going to the gym, spending evenings with his girlfriend. Life was ordinary, predictable.

Until the Fugitive Squad officers called.

“They were by my house in Stone Mountain and asked me to meet them,” Sonny recalls at our in-person interview at the Global Mall in Norcross. “I did. They served me a warrant for burglary, sexual assault, kidnapping, and aggravated sodomy. I thought it was a prank—until I saw guns and badges.”

“The paperwork said Thunderbolt,” he says. “I had never even been there. I didn’t know where it was. I had to ask somebody, ‘Where is this place?’”

In an instant, his life crumbled. The police weren’t interested in his protests, his paper trail, or the fact that he had reported his car stolen. All that mattered was that his vehicle had been used in a crime—and someone had pointed a finger at him.

What Sonny didn’t know then was that he had just stepped into the middle of a nightmare. A conman named Sterling Flint had vanished with his car. Evidence would disappear. There would be a flawed photo lineup and unreliable testimony. Prosecutors would seize on his skin color and his supposed religion to brand him guilty. And a jury would send him to prison for life.

“It didn’t matter what I said, what proof I had,” Sonny says. “This was post-9/11. I was brown. That was enough.”

What followed was the worst miscarriage of justice imaginable: 8,395 days—22 years and 8 days—behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

A Childhood Between Worlds

Sonny’s story began far from a Georgia prison. His father was born in Uganda, his mother in India. They married around 1970, moved to London, and eventually immigrated to the United States. Sonny arrived in January 1984, nine years old, trying to adjust to a new world.

“I realized over the years that the people I ‘won’ in life aren’t always blood,” he says. “The people who came into my journey—that’s who became family.”

He played Little League, made friends, and went to school in the Chamblee–Tucker area before the family moved to Stone Mountain. Yet even then, he felt a cultural divide. “I wanted my dad at my Little League games, but that just didn’t interest him,” Sonny remembers. “A child needs affirmation from their parents—I never got that.”

After high school, he drifted between career ideas—architecture, science, business—before settling into steady work. By 2001, at age 27, he was earning good money. “I was making about $1,000 a week after taxes. I was even planning to move to New York—$75 an hour up there,” he says. “My life was work, gym, girlfriend. That was it.”

Then he met Sterling Flynn.

A Car, a Conman, and a Catastrophe

What led to Sonny’s nightmare began with something as ordinary as letting a friend borrow his car. The friend said he was going to visit his mother in Beaufort, South Carolina. When he didn’t return on time, Sonny went to the man’s ex-wife’s house, where she gave him an address. Concerned, Sonny contacted police, who in turn reached out to Beaufort County authorities. They located the vehicle and had it impounded.

On November 19, 2001, Sonny went to Beaufort to retrieve his car. That same day he got a call from Sterling Flint. Flint suggested he drive the vehicle back to Atlanta, and Sonny agreed. On the way, they stopped in Savannah, where Flint took the wheel. “And then,” Sonny says, “the nightmare started.”

Flint agreed to drive the car back but went missing along the highway. Hours later, he called Sonny saying he would show up at Sonny’s girlfriend’s house, but he never did. The next day, Flint threatened to kill Sonny’s family. Alarmed, Sonny went straight to the police.

A week later, Sonny’s car was involved in a burglary in Thunderbolt, near Savannah. Flint was identified as the perpetrator. When police began looking for him, Sonny provided investigators with his girlfriend’s phone number. That tip led them to Flint’s girlfriend’s house, where police recovered stolen property from the burglary. And yet, instead of pursuing Flint, investigators inserted Sonny’s name into the case—and the nightmare became his.

When officers finally served Sonny a warrant, he was stunned. “The paperwork said Thunderbolt,” he remembers, naming the small coastal town near Savannah. “I had never even been to Thunderbolt. I didn’t know where it was. I had to ask somebody, ‘Where is this place?’ That’s how unreal it felt.”

The victim’s description didn’t match him—she initially reported her attacker as a Black male with bushy eyebrows, a bushy mustache, rough skin, and weighing 150 pounds. Lineups were flawed. One day she picked out Flynn. Another day she picked Sonny. In court, prosecutors presented only the lineup with Sonny’s photo in crisp clarity while the others were dark and blurred.

Meanwhile, evidence vanished. A recording of Sonny’s statement disappeared. The gloves supposedly used in the crime were mishandled by a detective who later lost his job and certification.

Flint’s girlfriend even admitted to Sonny that she had once been a Chatham County deputy, and her roommate at the time was a sheriff’s deputy. “That raised red flags later,” Sonny says, “especially when she became one of the main people saying I was involved.”

“In court, the DA said I was Muslim,” Sonny recalls. “I said I wasn’t. But this was post-9/11. I was brown, I was foreign. That was enough.”

He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Life in a Jungle

Prison wasn’t just punishment—it was survival. Sonny spent years in Georgia’s most violent facilities.

“You’re dropped into a jungle—lions, tigers, bears, rhinos—and must survive,” he says.

At Valdosta State Prison in 2016, someone tried to rob him in his bunk. “They stabbed me in the ear while I was asleep. It ruptured my eardrum,” Sonny says.

In 2018 at Hayes State Prison, the danger escalated. “I walked into a dorm for a medical appointment, and I was stabbed 12 times—my neck, my back, even my carotid,” he says. “Two officers stood there with cameras and did nothing.”

“I fought back and survived,” he continues quietly. “And then they wrote me up for fighting. That was prison: upside down.”

Despite constant threats, he never joined a gang. “I’d rather die standing than live on my knees,” he says. “If someone tried to take something, I fought. Otherwise, I kept my head down.”

What sustained him? “Hope,” Sonny says. “Knowing someone out there—an attorney, a friend—was still fighting for me. Without that, I would not be here.”

The Long Fight for Justice

DNA evidence should have cleared him early. In 2004, his appellate attorney paid $25,000 out of pocket for advanced testing. “I said, ‘I’m innocent—test it,’” Sonny recalls. The results excluded him. But courts ruled he was too late—that he should have done the test at trial, even though the technology wasn’t available in Georgia until years later.

“It was like the system was saying: even if the truth proves you innocent, you’ll still rot here,” he says.

Years of appeals failed. His father passed away in 2015 while Sonny was still inside. “I never got to see him. I missed his funeral. That broke me,” Sonny admits. The grief nearly swallowed him. In 2016, hopeless and alone, he tried to end his life. “I tried to hang myself,” he says quietly. “I was just tired. Tired of fighting, tired of waiting, tired of being forgotten.”

What kept him alive was hope—and the people who refused to give up on him. “What kept me alive was knowing someone out there was still fighting for me,” he says.

Finally, in a rare habeas hearing, his lawyers presented everything: the DNA results, expert testimony, even his trial attorney breaking down in tears.

“My trial lawyer said he has nightmares about me,” Sonny remembers. “He told the court he stays up crying. Hearing him admit that—it broke me and healed me at the same time.”

When Sonny testified, the courtroom cried. After seven months of waiting, the judge vacated his sentence.

“It took 8,395 days—23 years and 8 days—for me to get my daybreak,” Sonny says. “The darkest part of the night is right before daybreak. That’s what prison was for me—just darkness until then.”

Rebuilding a Life

At 51, Sonny is learning to live free again. He has a fiancée, Zara, who he says brings him peace. He enjoys cooking at home, visiting the Farmer’s Market, and simply opening the fridge whenever he wants.

“What I missed most in prison wasn’t just people—it was little freedoms. Taking a shower when you want, deciding your own day,” he says. “Now, cooking with Zara, seeing my mom smile—that’s enough.”

His mother, now 75, has welcomed him back. His father passed in 2015. “I never got to see him in prison. I missed his funeral. That hurt the most,” Sonny says.

Still, he holds onto forgiveness. “Am I bitter? No. Forgiveness means it happened, and there’s a lesson in it,” he says.

A GoFundMe was set up by the Georgia Innocence Project to help him rebuild his life

Seeking Justice Beyond Freedom

Freedom is only part of the battle. Sonny is now suing the Thunderbolt Police Department for perjury and missing evidence. He is also seeking compensation under Georgia’s wrongful conviction law—roughly $75,000 per year for the 23 years he lost.

He is also writing two books: Eastern Fathers, Western Sons, about his relationship with his father, and Life Without Justice, alternating chapters between himself and another wrongfully convicted man linked to Flynn.

And he dreams of advocacy. “I want to fight for women and children, for victims of human trafficking. That’s where I see myself,” he says.

But he also dreams small. “I’ve always wanted to live by the beach,” he adds with a smile.

A Message of Hope

Asked what message he wants to give others trapped in wrongful convictions, Sonny doesn’t hesitate.

“Never give up hope. If you believe you won’t get better, that mindset will kill you. Believe you’ll be okay,” he says. “Some of my best years are still ahead.”

Recently, Sonny stood outside the Chatham County Courthouse—the same courthouse that once sentenced him to life. He took a photo. “That was healing,” he says. “The place that stole my life—now I walk out free.”

Then he adds a reflection that carried him through the darkest moments: “The darkest part of the night is right before daybreak. That’s what prison was for me—just darkness until then. And after 8,395 days, my daybreak finally came.”